Last time, on Suspended Reason…

Why is [Moby Dick] white? He is white, and very much blank, because he personifies […] the indefinable, “the universe” rather than the world of people, that which refuses to be nailed down to a particular meaning. […] Each character has a different response to the unknowable white whale, who cannot be seen beneath the dark water, and even if fished out to the air and light, cannot truly be seen, because his form becomes distorted out of the water. […] Ahab in particular, the monomaniac eternalist, demands the impossible from the whale: that it reveal itself to him, its one final meaning, whether the universe cares about him or not, whether he is important or not.

quoted from Sarah Perry, “Light of the American Whale”

Contents:

- Introduction

- California Metaphysics

- Good Vibrations

- Hero as Enchanter

- Hero as Disenchanter

- End Notes

Listen to the playlist that goes with this essay.

Introduction

“Ever heard of Paul Gauguin? He was a stock broker in Paris and then he quit to become an artist. He sailed for Tahiti and never came back. He left behind his wife and kids, and when he got to Tahiti, gave half the island Syphilis.”

“Why are you telling me this?”

“Because there’s no such thing as paradise.”1

Lodge 49, S1E5

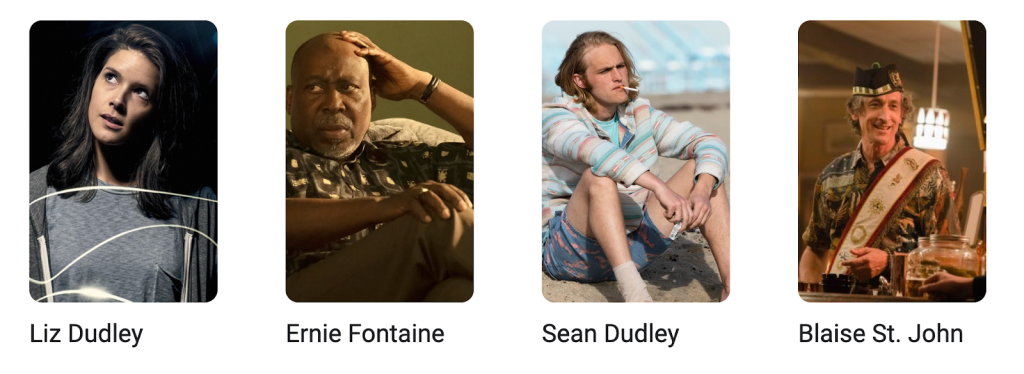

I have taken to watching AMC’s Lodge 49 in the bathtub. One of its lessons is this: There is no panacea, no paradise. Don’t be like Ernie and try to win it all at once. There is no “true lodge,” and there is no true system. Every portal to another world, that world will be flawed in some fundamental way, will have its own drawbacks and costs which demand patient and methodical mitigation, over time.

This is a known & accounted-for theme of American lit; it crops up all over post-War fic, but the most relevant predecessors for our purposes are Melville (Moby Dick), Steinbeck (The Pearl), and Pynchon, on whose The Crying of Lot 49 our Lodge 49 is loosely based.

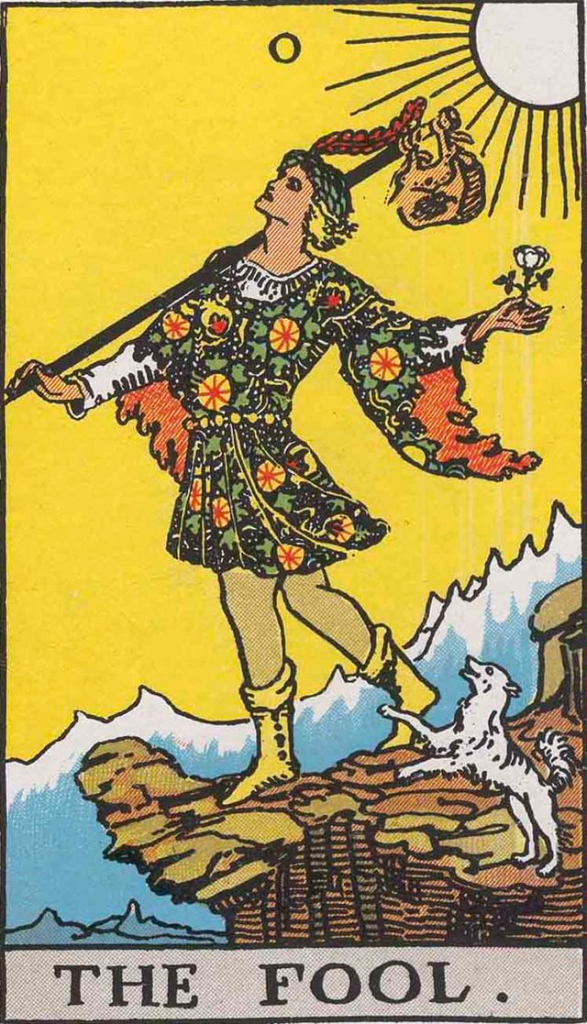

But Lodge 49 takes these ideas somewhere less trod. It notices that Ahab provides a quest and living for his crew; that it’s his fanaticism which dooms him, and not his passion. It sees in the figure of cringey Don Quixote something more than ridiculous. It gives the tarot’s Fool, teetering on the edge of a cliff, a torch of faith that few else carry.

Initially the tube series—like its namesake—presents itself to us as mystery, a bit of California noir. A secret society, a mysterious seal, a death in the family; a protagonist constantly on the threshold of understanding. And over the course of its two seasons, we do get something approximating a detective’s quest. But our protagonist Sean “Dud” Dudley turns out to be a very different sort of hero from the detective of noir;2 and just as “invention,” etymologically, once meant something much closer to “discovery,” Dud’s arc illuminates the world-constructing side of world-searching. Our hero creates meaning as much as discovers it; it’s his act questing itself,3 and not its end (for there is no end…), which brings him closer to heaven. Dud is a world-building prophet, a metaphor-making poet, a communer with the world of spirit.

Max Weber, theorist of charisma and disenchantment, writes in his discussion of prophets that (emphasis mine):

Prophetic revelation involves for both the prophet himself and for his followers… a unified view of the world derived from a consciously integrated and meaningful attitude toward life. To the prophet, both the life of man and the world, both social and cosmic events, have a certain systematic and coherent meaning. To this meaning the conduct of mankind must be oriented if it is to bring salvation, for only in relation to this meaning does life obtain a unified and significant pattern.

We begin with Christ, the great prophet and worldbuilder—who introduced new moral and conceptual primitives; who as much created truth as discovered it; who preached of another world, and by it, bridged heaven and earth.

We begin with Dud—beachcomber, detectorist, card-carrying member of the Longhair Coalition—strolling along the shore of the ocean he once happily surfed. Ever since his snakebite, on a surfer’s pilgrimage through Guatemala, he’s been unable to leash up for dawn patrol, the ankle wound never fully healing. Cast out of Eden, his Father lost at sea, we find him searching for gold in the white sands of Long Beach, pacing along the break of a former life.

Oh Dudley! Twice bitten, twice born; twice orphaned, twice ousted. Who purifies waters and carries the faith. Dweller of the past, orphan of a drowned world, torn between his desire to stay among the ruins, or find some new world to settle. He knows not future lands, nor speculates on their nature, nor tucks away savings to improve their prospect. Keeper of vibe; prophet and myth-maker; storyteller and priest of hyperstition and pack animal of narrative, here we see him in his darkest hour.

Pool cleaner, who keeps the waters clear! Who uncloggeth filters of drowned rats! Surfer, who rides waves of disruption without wiping out, for the thrill of it! Snake, who lurks in the brush, and bites at the ankle of the Fool, whose head is in the clouds, and whose mind is on the distant surf! “We’re water people. You needa get back in the water.” Back on the board, back to the waves—but not yet; the story’s just beginning.

California Metaphysics

Much has been said & made of Californian Ideology, that West Coast blend of techno-optimism and liberatory self-expression, psychedelic vision and futurism which guided Mondo2000 and Whole Earth, Burning Man and Apple, which fueled Stewart Brand’s long anti-career arc and saw John Perry Barlow straddling the Grateful Dead and Electronic Frontier Foundation.

But there is also a California Metaphysics,4 not so much a coherent position as an axis of conflict between NorCal and SoCal, its Mason-Dixon cutting somewhere between Pismo Beach and Los Olivos. Silicon Valley5 and Haight-Ashbury versus Hollywood and the Elysian Heights. Santa Cruz joint smokers clad in drug rugs, versus the bronzing dab-men of Venice Beach. In the balmy Mediterranean climes south of Pismo, a classical attitude towards masks and persona reigns. Personhood itself is a front, a face, a performance. Where a NorCal hippy might grow out body hair in a back-to-nature move, some reclamation of lost authentic states, the SoCal hustler sees one more fashion trend, one more set of symbolic postures. (“The Jesus-look is in.”) Peel away the surface, some Californian metaphysicians (shrugging) tell us, and you’ll just find another surface. The landscape of the interior is one more social strategy, a disposition in service of performance. Or—if some hidden and privileged interiority is ceded—it’s looked down upon the way a nineteenth century cranium-measuring aristocrat might condescend to natural impulse. Surfaces are ennobling, aspirational. Get back to nature and all you’ll find are animals.

Not that either camp are proper relativists. The promise of psychedelics lies in their ability to de-naturalize the ready-at-hand, to present alternate surfaces and make explicit our structuring interpretive schemas. Beach-bum SoCalites are liable to hedonistic languor, soaking in the brightened colors and tracer viz, tripping just one more performance. NorCal hippies, though, are liable to take those new surfaces and slogans as deeper and underlying truths, to take every new perspective as “the” perspective. Until you dose, you just won’t get it. LSD is paradisal, the trip either life-changing inflection point, or the sort of temporary glimpse of Eden’ll drive a man insane just chasing it forever. Everything changes—until the next morning, when the newly converted fall back on old habits or get reabsorbed by intelligent social webs. Because men are made by their moments, habits are solutions to problems, and none of those problems have gone anywhere.

Pynchon’s novels, which in content treat Californian Ideology and its failings, in form play out a strange psyched-out, ontologically-hip rendition of California Metaphysics’ mystico-philosophical stance. His detectives chase after some transcendental breakthrough like a Flammarion engraving6—some vision of the Other Side, the true nature of things, an Authoritative Representation. All they manage to find is one more partial vision. That’s what a representation is, after all—partial, in both senses of the word. Pynchon liked to quip, in the golden old days, that Murphy’s Law was just a natural corollary of Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. Representations leave things out,7 and then the left-out excess rises up to spank the hubris of the would-be systematizer, see also James C. Scott.8 Plus there’s the time-honored problems of pragmatism, the “What would it even mean to find a true metaphor?” that rears its head alongside the 20th century’s “reflexivity”—all complicating the epistemology of a 19th century Arthur Conan Doyle. Hence Pynchon’s protagonists, and the heroes of Lodge 49. Every time they think they’ve found a settled answer, it transforms again into questions. Every time they think they’ve found a window, it turns out to be a mirror.9 Rooms just open up into further rooms, an infinite series of chambers and backrooms without center or panoptic view. Everything solid turns to smoke; every liminal threshold is just another stage transition masquerading as transcendence. No “breaking through,” only a slow progression through different, fragmentary views. The hero searches vainly for a synthetic dream that unites these fragments, but his text-world refuses to yield a culminating vision of the universe as “blindingly One.” His greatest error is getting stuck in dichotomy, in the artificial boundary of a binary concept; his greatest error is his lack of belief in the reality of an excluded middle.10 So The Crying of Lot 49 ends with Oedipa, stuck in ambivalence, oscillating between two poles, paralyzed in the misimpression that she must commit—commit absolutely—to one interpretation or the other:

…how had it ever happened here, with the chances once so good for diversity? For it was now like walking among matrices of a great digital computer, the zeroes and ones twinned above, hanging like balanced mobiles right and left, ahead, thick, maybe endless. Behind the hieroglyphic streets11 there would either be a transcendent meaning, or only the earth… Another mode of meaning behind the obvious, or none. Either Oedipa in the orbiting of a true paranoia, or a real Tristero. For there either was some Tristero beyond the appearance of the legacy of America, or there was just America…

Nor is the act of peeling layers back a neutral act of voyeur-observation. In getting involved, the detective reflexively shapes his world as much as he unveils it. Jake Gittes, in his Chinatown voyeurism, ends up an active player and pawn for the forces that be: first, his photographs are leaked to the press, causing a scandal; second, we realize he has been set up, used as an instrument in a ploy. Here the private eye—as voyeur, photographer, and storyteller—becomes a stand-in for the artist. As much as he is an instrument of truth (his idealized self-image) he is also a tool of power.

Next, Gittes finds out the man he had photographed is dead—drowned, to be precise. In fact there is an epidemic of drowning happening, drought be damned. All these people are dying of (symbolically speaking) the complexity of reality—choking on the truth, which they are murdered for seeking, or partially witnessing, or uncovering. Gittes, who never learns, his past foreshadowing his future: “You can’t always tell what’s going on… I was tryna keep someone from being hurt, and I ended up making sure she was hurt.” Huston’s Noah Cross wants so badly to own, so badly to possess the future—symbolized and literalized in daughter Evelyn—that he destroys said future, “taints the well,” bleeds the valley, contaminates the bloodline with incest. The traumas and deformities of inbreeding: another parable against totalizing systems, against the total control that admits no truck with the unfamiliar.12

Some read Pynchon’s fiction as arguing the old truisms—journey over destination, Mom incanting for the backseat—“in the end, what matters is the friends you made along the way.” The search & discovery of pattern, more than any pattern in particular. The quest for knowledge, over any final revelation. “Characters oscillate between mundane, deflationary accounts, and more sacred, mystic ones.” “Behind the hieroglyphic streets there would either be a transcendent meaning, or only the earth.” All this is present in Lodge 49, but doubled-down on. Pynchon, as a transitional figure between modernism and postmodernism, is ambiguously read as either embracing the reality of a hidden world (which cannot be known in its entirety), or as disavowing the idea of hidden truth itself, replacing it with a PoMo plethora of perspectives. My personal reading veers toward a vaguely postmodern “both/and” (compared to, say, the modernism of Chinatown), but for our purposes, the difference is irrelevant, because we are interested in the additional (if we must, “metamodern”) step that Lodge 49 takes.

So we have two problems, which is to say two opportunities, that are presented by twentieth century epistemology.

First is the [problem | opportunity] of a monotheism’s collapse, where “monotheism” is something like the belief in the possibility and desirability of a single totalizing, all-encompassing system. (The monotheist, here, is much like the “fanatic” or “partisan” described previously, who, in Chesterton’s words, lives “in the clean and well-lit prison of one idea.”) One response to this failure is polytheism, or an “ecology of practice.”13

The second [problem | opportunity] lies in the observer effect, the transformation of reality directly and indirectly through its perceptual-hermeneutic structuring. Map altering territory, map making itself true. One of the opportunities this problem raises is the possibility of enchantment.

Good Vibrations

…the Muzak had been seeping in, in its subliminal, unidentifiable way since they’d entered the place, all strings, reeds, muted brass…”

The Crying of Lot 49

I love the colorful clothes she wears

And the way the sunlight plays upon her hair

I hear the sound of a gentle word

On the wind that lifts her perfume through the air

I’m pickin’ up good vibrations

She’s giving me the excitations (oom bop bop)

“Good Vibrations” (1966)

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Arthur C. Clarke (1962)

All hail the return of the 60s—enter a partial translation of magic as vibework. Magic and language have been inextricable from the beginning, and it might be just as true to translate magic as communication (as manipulation)—but then there is also the close historical association between magic and music, enchantment and incantation; the bard tells stories,14 strokes his lyre, casts a spell on his fire-hypnotized audience. Magic is communication, sure, but rarely the explicit kind. The DJ is a sorcerer, a shaman, a manipulator of vibe, “with a headset clamped on and cueing the next record, with movements stylized as the handling of chrism, censer, chalice might be for a holy man…” (Crying of Lot 49). Magic, more often, is a form of subtle communication which lurks in ambience and mood—made all the more powerful for being implicit rather than explicit, since it lurks in the situational framing and unspoken premises which are difficult to audit, and difficult to bring to the arena for contestation. It is a communion with the psychic world of Yetzirah, realm of dreams and emotions and the flow of cognitive energies—and therefore frequently linked to charisma, rhetoric, body language, conceptual framing, poetry, and what sociologist Randall Collins calls “emotional energy.” (“Encounters have an emotional aftermath… EE ebbs away after a period of time; to renew it, individuals are drawn back into ritual participation to recharge themselves [through the sharing of a common mood or emotion]…”)

Vibes may be attributed to worlds, or to world-regulators (crudely, “agents”) who are in possession of world-orientations. Such orientations straddle social-strategic stances and old fashioned, intrinsic, good-regulator adaptedness; like all models, they encode information about the world-environment they emerge within, from the structure of symbolic-capital payouts to the patterned regularities of physics. A vibe appears, to the perceiving subject, as a particularity of feel—a layering of sensory-array emergences with a primal attraction and repulsion, with emotion and learned association and memory and inference. The drugs we take change both the vibes we read off the world, and the vibes we write to it, and neither can be separated from the other, nor given precedent—each just feeds endlessly back through its counterpart.

By “magic,” I mean only an acknowledgment that we are sensing organisms, living not in “reality,” but in narrative and inter-subjective illusion. An alternate factoring of magic might define it as the social construction of reality. In our compressive coarse-graining, we necessarily end up living in moods and their “colored beads.”15 Or as Ioan Culianu, historian of Renaissance magic, writes: “Aristotle denied that that it was possible to think without phantasms. Now phantasms are colored emotionally, and though they are able to occupy any space, the places that suits them best is the ‘heart,’ for it is the heart that feels emotions.” Moods are something like phenomenological projections (or “compressions”) of worlds, so that we may speak somewhat rigorously of “vibing towards a new world.” This, more or less, is what is entailed by a polytheistic ecology of practice; this is why Melville’s whale is white, white being the color of all spectrums at once, synoptically visible as a single color.16

Vibing, as a form of communication, is an embodied means of holistically and compressively conveying information about the state of the world via an individual’s emotional orientation to that world-state. Implicit in stress or anxiety is a perception of the world, based on experience, as threatening or uncertain; it’s not surprising that stress and anxiety (like all moods) are highly contagious, insofar as their spread is a form of social learning. And the same is true of projected calm as an indicator of safety: we alter our orientations to the world on a “rational basis,” on social computation, assuming others may know things we don’t know, have seen things we haven’t.

Skaters, swingers, stoners, and surfers (e.g. Dud)—these are subcultures that hold up “vibe” above all else, their members operating based on some intuitive, felt and subtle sense, rather than logically auditable or “rational” (read: verbally justifiable) principles. They are sensitive to ripples, rather than being manipulators of syntax. They are also all counter-cultural movements; this prioritization of non-verbal mood seems to go against the dominant value hierarchy of our time (even as everywhere we exalt its abstract concept in surrogation games…).

In both Eastern and Western forms, magic involves a wielding or redirecting of energies. Mesmerism, emerging in the Rosicrucian period, claimed to alter us by means of an invisible and vitalizing force, which connects all life. The Arab philosopher al-Kindī held that we live amidst an invisible network of radiations—emitted by all objects, exerting influence on one another through rays, making their presence known.17 New Thought, an old-timey American transcendentalist splinter, believed that people were constituted of a pure energy, which attracted or repelled people and events. We may lecture on incommensurability, but are these ideas so hard to appropriate into a technoscientific worldview? Similar models of vitalizing forces, from élan vital to qi, are old as human thought. Let us pay our dues both to the wisdom of the ages, and the metaphysics of modern scientists: there is such an energy, and it obeys the laws of physics; it is an interpersonal energy, a kind of communication, an intense cathexis of “reading and writing” that occurs when we enter proximity with other organisms. Insofar as we believe in placebo effects, or behavioral economic concepts of “priming” and “nudge,” we have already ceded much of the magical picture.

Frequently, this energy work is broken up into intra-subjective and intersubjective practices. To the intra-subjective magician, psychological theories are (again) not neutral but active; they are organizing principles, and in the same way that an organization, adopting a theory of itself and its working processes, ends up transforming its own workings, so too do our theories of ourselves. This is a more occult model of psychology, opposed to the orthodoxy of depth psychology more widespread in the West. Depth psychology posits a fixed set of unconscious impulses, beliefs, and desires, some immoveable “personal character,” which will inevitably “leak out” in behavior if not addressed, and which should therefore be brought into the light for prolonged examination. An intra-subjective, more “magical” feedback model, meanwhile, is more inclined to treat consciousness as something infinitely malleable, something grown and pruned like a plant, something created through curation. The more attention one gives to evil and base impulses, the more they grow and consume us. We purify our thoughts to purify our world. This view was more common in a pre-Freud world.

The central insight of the intersubjective magician, meanwhile, is a recognition the squishiness and reflexivity of world-states—that my state depends on your state depends on my state; that our expressions are representations of states, which become the basis of others’ expressions and representations. In contrast to the magician, the uninitiated (those who must follow magicians, since they cannot yet make their own magic) look to others for solidity. The uninitiated ask their lovers, in pillow-talk, “What are you thinking?” and “How are you feeling?”—hoping to neutrally query for steady, reassuring ground, deferring the work of creating a moment’s “mood-reality” onto the other. The magician, on the other hand, speaks to create the moment’s mood-reality. A certain charisma is attributed to individuals who make the most compelling shows of solidity, which often means those individuals who are themselves the most self-deceiving (since they have not yet come to terms with their own squishiness, let alone that of the world). These individuals are not yet true magicians; their naivete, and the fanatical partisanship which results from it, must first be overcome; the true magician must pass through a valley of relativism in order to reach a peak much higher than self-deception. That peak is faith.

William James, “On the Will to Believe” (1896):

Turn now from these wide questions of good to a certain class of questions of fact, questions concerning personal relations, states of mind between one man and another. Do you like me or not?—for example. Whether you do or not depends, in countless instances, on whether I meet you half-way, am willing to assume that you must like me, and show you trust and expectation. The previous faith on my part in your liking’s existence is in such cases what makes your liking come. But if I stand aloof, and refuse to budge an inch until I have objective evidence, until you shall have done something apt, as the absolutists say, ad extorquendum assensum meum, ten to one your liking never comes. How many women’s hearts are vanquished by the mere sanguine insistence of some man that they must love him! He will not consent to the hypothesis that they cannot. The desire for a certain kind of truth here brings about that special truth’s existence; and so it is in innumerable cases of other sorts. Who gains promotions, boons, appointments, but the man in whose life they are seen to play the part of live hypotheses, who discounts them, sacrifices other things for their sake before they have come, and takes risks for them in advance ? His faith acts on the powers above him as a claim, and creates its own verification.

*

In the most reductionist, rationalistic terms available, we can think of vibes as coherent arrays of costly signals. An array might consist of body posture, facial microgestures, vocal tremors and tonality, the actual semiotic content of utterances, clothing. One of the most load-bearing forms of costly signals, in human communication, is the information signal. A given shibboleth—perhaps the pronunciation of a word, or an item of clothing—is easily performed granted one knows to perform it. What is costly and difficult to obtain is the tacit, procedural knowledge itself. It is difficult for a fed to personally infiltrate a countercultural group, because of how lacking in relevant shibboleths of speech, attire, and opinion he is. (Thus he more frequently resorts to turning and bribing insiders.) The best undercover agents spend years or decades gaining intimate familiarity with the worlds they live in; they come to be proper members of those worlds, not so much acting anymore as living their role; and here of course enters the danger of the long-embedded agent, who is helplessly compromised by his time undercover.

Vibe in particular requires not just a knowledge of a single shibboleth or information signal, but requires a coherent array of such signals, presented alongside a compelling expressive-emotional array. To fake a signaling display that is as high-definition as reality is nearly impossible—a single detail can bust you, a single hand gesture or speech pattern lifted from the wrong culture, so unconscious you don’t even realize you’ve been busted; see e.g. Oedipa’s attempted interrogation of Yoyodyne engineer Stanley Koteks, where she tries bluffing subcultural familiarity to get information:

She took a chance: “Then the WASTE address isn’t good anymore.” But she’d pronounced it like a word, waste. [Kotek’s] face congealed, a mask of distrust. “It’s W.A.S.T.E., lady,” he told her, “an acronym, not ‘waste,’ and we had best not go into it any further.”

But other small details, like the quiver in her voice, her nanosecond hesitations before speaking, give her away as well. Her detective quest proceeds by means of scribbled notes in a little memo book—“Shall I project a world?” next to “Box 7391” and a sketch of the muted Tristero trumpet. She’s writing to read and reading to write—assembling a text-world to decipher the text-world, and vice-versa.

Hero as Enchanter

[The euphantasy] may be resembled to a glass… There be again of these glasses that show things exceeding fair and comely, others that show figures very monstrous and ill favored. Even so is the fantastical part of man (if it be not disordered) a representer of the best, most comely and beautiful images or appearances of things to the soul… Wherefore such persons as be illuminated with the brightest irradiations… they are called… “euphantasiote,” and of this sort of fantasy are all good Poets…

George Puttenham, 1588; quoted in Culianu

Meryl believed there were two kinds of Alchemists. First is the charlatan who was just looking for a shortcut. And the next was the true philosopher, who views that world out there as a beautiful text just waiting to be deciphered. We just have to learn how to look at it with the right eyes.

Blaise St. John, Lodge 49

The first, and most basic, form of enchantment, is enthusiasm. We can’t help but enjoy being around those people whose optical arrays scream pure possibility. We get to see things through their eyes—temporarily, but with enough exposure, who knows what’ll rub off. This appeal underlies the manic pixie dream-girl archetype and her male equivalent,18 refreshing fatigued worldviews, offering alternative interpretations. Cf. the old koan, anxiety just impoverished imagination.

Enthusiasm is the positive-valenced emotional response to a connected and safe-enough universe. To the indiscriminately, amphetaminically eager, everything and everyone is potentially relevant. All information is potentially useful. All signs point to something, if one can only discover what. This sensation of connectivity and entailment is part of what we mean when we talk about meaningfulness.

The second form of enchantment is merely an admission of mystery in the world. “Mysticism keeps men sane,” Chesterton writes, in his extended attack on the assured certainty of atheist-materialists. “As long as you have mystery you have health; when you destroy mystery, you create morbidity.” Materialism, on the other hand, is a totalizing set of metaphors that admits no alternative possibilities and considers everything theoretically explicable within its metaphorical frame. It is surprisingly common among the college-educated to believe that a majority of what could possibly be known has already been discovered. Fields as primitive and nascent as psychology and medicine are regarded as mostly solved sciences, rather than more or less medieval—their speculations about complex emergences passed around as infallible fact. Chesterton:

Materialism has a sort of insane simplicity. It has just the quality of the madman’s argument; we have at once the sense of it covering everything and the sense of it leaving everything out… [The materialist] understands everything, and everything does not seem worth understanding. His cosmos may be complete in every rivet and cog-wheel, but still his cosmos is smaller than our world.

G.K. Chesterton, “Orthodoxy”

Many may object to this critique of materialism as Catholic-PoMo woo—but it’s not even that I think materialism “isn’t true,” so much as I believe that most domains in the world we care about—morality and communication and emotion and relationships—take place at such a high level of complexity that we cannot—certainly not at present, and perhaps not at any time—begin to make sense of them through material metaphors, using the procedural rules associated with physics. We are left either using materialist metaphors loosely, to describe emergences—in which case we are armed with an impoverished conceptual toolkit, having radically purged all traditional implements—or else we are left unable to make sense of the most pressing patterns and dynamics in our lives. This is a common failure mode of rationalistic thought; its reductionist, Occam’s razor aesthetic is meaningfully opposite the worldbuilding instinct of the hero-as-enchanter. In its minimalism, it revels in purging all elements of a system that cannot be demonstrated as load-bearing; the resulting descriptive system is anemic in its monotheism, thin rather than thick.

There are many true ways a story may be told, for all stories are at best partial representations, which allow other partial representations to challenge their authority. There are many true ways a story may be told, yet sometimes the world unfolds quite differently depending which is chosen. We may fashion ourselves noble casters, but casters and rhetoricians we remain—whether or not we try to be. If we do strive, we are racked with the guilt of responsibility, an inescapable part of adulthood. If we do not strive, we are still rhetoricians, but clumsy ones—either ineffective, or pointed towards evil, unconsidered ends. All true moral decisions are Scyllas & Charybdis. We say little charms on those we parlay with; perhaps we hex them, lay a guilt trip on them, give bad advice. Sometimes, in great storms of anger or passion, we send waves of half-controlled energy, speak words which will drive them to sleeplessness, fixation, induce anxious attacks or stir them into negligence. The sorcerer’s apprentice is prone to misusing his amateur magic; he lacks the restraint, and the higher vision of purpose, which will characterize his years as master.

When we first catch Dud, series premiere, he’s reading Dune. A book about a boy whose world falls apart when his father is killed; who is then exiled from his culture, and finds himself among a new people, learning their ways but also invigorating them in return—becoming their prophet and torch-bearer.

This is Dud’s story. The prophet—as clerical variant on the sorcerer, guiding descents into the underworld and catalyzing community—works by mythologizing of the present, by imposing timeless and recurrent structures onto timely specifics, and transforming the immense panorama of futility and mundanity into something with shape and significance. His is the projection of eternal recurrence on the constantly new, of a “world order that transcends individuality” and which—in this transcending—gives the individual back to himself.19 The metaphorical structure drawn upon becomes a locus of collective coordination, the basis and based in a structure of values—hence the close historical connection between religious and moral systems. As a wizard travels with wand, so the prophet carries a torch of faith, by which he illuminates a path through worldly darkness.

Dud is a Holy Fool, and thus aligned with the seeker archetype; the twist is that he is both initiate and initiand. The twist is that by seeking—by learning proper sight20—he authors an alchemical transformation, a more golden world.21 This enchanted vision is not some flighty, spur-of-the-moment choice, which when made instantly transforms our view. Rather, it is a painstaking process of building a structure of perception, likened to Judith Butler’s model of gender performativity with its emphasis on repetition and acculturation. The question is: What do you want to create with your vision? At the beginning of the series, Dud is a detectorist: He’s searching for gold and precious metals. What he needs to learn is how to make gold himself. Gold like the rays of the sun. And some of his narrative creations are duds.

The artist himself is a hero-as-enchanter; his works (as partial representations) are initiatory texts into a way of perceiving the world. “According to [this] concept, art’s purpose is monere, and a novel offers to its reader an example of coherence and order that rebukes the confusion of life and offers an alternative example”22—in a phrase, value clarity.” As a totalizing system, this ordered coherence is a fantasy; as a supplementary mood, as novel and additive (rather than substitutive) framework, it’s as real as any alternative. This is why we so often use artists’ names as shorthands for ways of seeing: the Lynchian, the Kafkaesque. In the second section of the first book I write, I take to inscribing a Novalis quote: “The world must be romanticized. In this way its original meaning will be rediscovered. Romanticization is nothing but a qualitative realization of potential.”

*

You swore you’d never fall. You swore you’d do it different. You wanted nothing less than what you believed was possible: to rise to every occasion; to be your best self all the time. What you didn’t count on was how all-the-time it was, the way occasions bled into each other and layered, so that failures and shortfalls spilled endlessly into the future. You wanted to sustain enchanted vision, the meaning-laden view that confers wisdom, but what you didn’t reckon on was how constant the interruptions, disruptions, challenges, and crises of faith would be. How constant the impositions of alternate worldviews; how powerful the accumulation of inertia, of habit, of nature and nurture. The debts just keep racking, the regrets never really fade, and the law of compound interest slowly crushes you.23 One last gig, one last show, one last fight—a way to set things right. The search for deus ex machina, the world’s final account-balancer. For panacea, and the paradise it promises.

But enchantments are always temporary; they vanish faster than you can believe. “Perhaps we’ll meet again in that place where all circles vanish. Or you can email me, either way.” Every time a glimpse of the other side glimmers through, our routines of action and perception reduce it to the known. Every psychedelic vision reinterpreted as hallucination. And sometimes it seems personal, like everyone’s out to disenchant you—but it’s just their own disappointments pushing back against the offense and violence of your alternate world-frame. Some folk seem particularly fond of cynical reduction and dismissal, and they’re the most hurt of all. Colloquially, we call them “bummers to be around”; they score higher in neuroticism, higher in intelligence, and are frequently seen as more intelligent solely for the cynicism of their stance, which is often mistaken for “gritty realism” instead of depression. (This conflation is best treated by Mark Fisher, in his writings on depressive ontology.) But illusions are meant to be socially sustained, so that your moments of exhaustion can be met by energy, so your moments of doubt can be met by belief. That’s what a group is, really—rallying the ball of narrative back and forth. Heroic efforts inspiring surging tides. And that’s our Dud, hero of Lodge 49. Constantly asserting the enchanted interpretation of his world, and trying to rally others around it. “Dud is a searcher, a willing participant in his story. Everything he does is moving himself forward; he is his own engine; no one else is making things happen for him or to him.”24 Constantly countered by “get real,” the resigned world-atheism of those around him.

“If only Larry could see this. His knights gearing up for a battle, attended by their squire.” Sure, it’s cringey this language, Long Beach Lynx Lodgers LARPing as chivalric vassals late in the second season. But that’s not all the show thinks. The show thinks it’s important, in a life-or-death way, to choose romanticizing frameworks. Thinks this is one of the roles of poetry. A letter from the original Lodge 1 in London, announcing the arrival of an emissary to sanction succession rites, announces said emissary’s arrival “within a fortnight,” and Ernie chews on that last word, really savors it, repeats it to himself, after Larry’s gone, like a minor magic spell that’s just been cast on the next two weeks. Or consider the pinball machine, a Lodge staple frequented by Dud—how it’s made more compelling by its world-flavor. Mechanically speaking, pinball machines are all roughly similar, but they get enchanted by thematized graphics and stickers, the programmed audio recordings and decorative molds and hints of lore that together add up to immersive world-feel.

But it also casts enchantment as carrying a cost, its concomitant risks. Both the Lodge’s Sovereign Protector (a symbolic Pater), and Dud’s own literal father, rack up enormous amounts of debt while maintaining the public illusion of S’all Good Man. They present an enchanted world that others take on credit; in the process, they rack up a mountain of debt. What does it mean that Scott—representing a more protestant, adult notion of responsibility—makes his first act as Sovereign Protector to call lodge members’ bar tabs? It’s too sudden and too dramatic a come-to-earth moment, members suddenly on the hook for thousands; the effort predictably fails. But the ledgers still need balancing.25

Burt, meanwhile—pawnshop broker and bookie—is the closest thing we get to God in this show, and it’s no coincidence he’s a debt collector whose lineback-enforcer is named Hermes, divine messenger. Most of his appearances are mundane: reading the paper, munching sandwiches (“as above, so below”), stoically receiving verbal abuse (first from Father Dudley, then from Son). It’s only at the show’s conclusion that his greater role is hinted. “To do my job,” he tells Dud,” you need to see a long, long ways.” Burt’s the one who distinguishes between real gold and fool’s gold.

When Dud discovers a hidden tunnel in the alchemist’s chamber, gold dust from the portal entrance rubs off on his fingers. The in-world aerospace giant Orbis, at its mid-century economic peak, floods Long Beach with its own system of currency, with a simulacra of gold coins. What gives these cheap tokens value? A structure of belief. Companies, in Lodge 49, are also belief structures; alongside the family, ever-diminished, they’re the default meaning structures of modern life. When Dud is gathering energy, rallying the troops, for some great border-crossing quest, he is up against the practical economic and professional realities that beset his lodge-mate Ernie. And Ernie has a moral leader of his own—a boss at West Coast Super Sales that quotes Keats and rallies the troops to great deeds of salesmanship. He’s corny, sure—but imagine the job without him.

Hero as Disenchanter

The Christian is quite free to believe that there is a considerable amount of settled order and inevitable development in the universe. But the materialist is not allowed to admit into his spotless machine the slightest speck of spiritualism or miracle.

G.K. Chesterton, “Orthodoxy”

Classic noir sensibility, by contrast, is identified with a depressive, disenchanted, “realistic” and Existentialist orientation, an “underlying mood of pessimism which undercuts any attempted happy endings” (Robert Porfirio). Its private eye lives nocturnally in an urban underworld, hiding himself in shadows. He is an Outsider who has rejected all social systems and their requisite illusions. His version of moral support is a glass of bourbon. His is a grim business of disenchantment—snapping the incriminating infidelity shot, messenger of death for the fading half-life magic cast by marriage vows. He himself is long since disenchanted—is a cynic, sees the world as ethically irrational, some sick joke. His is a chore of capturing and exposing, rather than sheltering. His tragic flaw is a fatal attraction to some hypnotic phenomenon, some Siren-song, which he attempts to possess or capture, but which perpetually eludes him. His principle affect is non-affect, a detachment or cool; he is a dandy in the Baudelaire-Cavell sense: he carries “an air of coldness which comes from an unshakeable determination not to be moved…” Whereas, in Lodge 49, Dud is heat, and Liz is ice, always climbing into freezers, jumping off boat at open sea and using an Orbis fridge as a life-raft. Dud’s nickname for her is “Lizard”—i.e., cold-blooded.

(Warm-blooded organisms, by contrast, produce their own heat. One elemental interpretation of this show would have Dud as cast out of his native element—water—and forced to master the other three elements—air, earth, and fire. Earth relates to reality-grounding, something Dud’s still working on when the second season wraps. Fire symbolizes the metabolizing of world-material in order to stay alive, to provide heat for those who crowd and circle up around you; this at least, Dud’s beginning to master. )

When the sacred manifests in the profane and everyday, it confronts us with its unfamiliar logic, with its belonging to “a wholly different order” (Ed Mendelson, “The Sacred, the Profane, and the Crying of Lot 49”). And yet the sacred can only instantiate itself, can only show itself to us, in this world, through (i.e. embodied as) the profane. Thus “everything in [Lot 49] that points to a sacred significance in the Trystero has, potentially a secular explanation.” Oedipa is left, “at every moment,” with the choice of affirming or denying the sacredness of what she sees. This duality, this both-and masquerading as either-or, is practically a refrain in Lodge 49. Dud knocks on the door of the Lodge for the first time, unannounced, as is told by Ernie they’ve been “expecting” him—that time-honored greeting of the mystic-mentor, long foreseeing his student’s arrival. But then it turns out the Lodge is just expecting a carpet-cleaner to arrive, and took Dud to fit the bill. When Avery bids adieu to Blaise, he quips in a put-on British accent, “Perhaps we’ll meet again, in that place where all circles vanish.” Then he drops the bit: “Or you can email me; either way.”26 Perhaps the primary symbol of this duality is the unicorn, which is brought up explicitly as an example of a mystical or supposedly fantastic creature who also, simultaneously, exists in real form here on earth, in the rhinoceros (S1E427) and the narwhal (S1E8, S1E9).

This duality means you have some choice over which set of signs, which narrative you want to live inside. Dud and Liz, twin siblings, end up consistently making opposite choices. So watch how this interaction goes down between Liz and an acquaintance-psychic (played by James Urbaniak of Henry Fool28), when they bump into each other on a bluff trail, overlooking the sea. “Tony the Psychic.” “I knew you’d be here.” “No, you didn’t.” “You’re 100% right. I walk the bluffs every day. It’s just a fateful coincidence you happen to be here.” “No, it’s not.” Here’s the money shot: “Well, in the most literal sense of the term, it absolutely is a coincidence;29 we can assign it whatever meaning we want after the fact.” “OK. I assign no meaning to it.” This is about as explicit as it gets, in terms of a statement of the show’s philosophy—but watch what happens next. First, he shows vulnerability, to create space for her to do the same.

Tony the Psychic: “Ever since I turned 40 I get terrible claustrophobia. I kicked out the back window of my friends’ Yukon the other day because I was stuck in the middle seat and my buddies wouldn’t let me out.” Now it’s her turn. “I’m a water person.” “They say the ocean is a mother. We all come from the sea.” “I’ve been spending time in freezers. The cold relaxes me. I have dreams about blizzards and ice sheets.” “Thermodynamics. The cold is an endpoint. The cold is the abyss.” This is that old Pynchon theme, entropy. On the other side is death. “The abyss isn’t death. That’s just a fable God made up to keep up away from the truth.” If you’re saying, wait a sec—the metaphorical logic of this essay is contradicting itself, you keep saying the abyss is death and now you’re backing out? Well, I didn’t say it, he did, because his job isn’t telling “the truth,” and insofar as it is, “the truth” isn’t consistent, not at this level of coarse-graining. The only inter-consistent descriptions of reality we have are laws of physics. Tony’s job is telling people what they need to hear, which is its own sort of truth. That’s why he’s a psychic. Liz doesn’t need a death-wish metaphor. “Maybe you’re just drawn to what other people fear. That probably makes you more alive.” The other part of is his job is timing; Tony walks off, giving the alternate framing the space to make itself felt. Why did Liz’s mother go out for night swims? Was she terrified? No: she loved it. She was fearless. The great uncertainty, the gnostic world lit only by dim, distant stars. The dandy, cool as ice, nonetheless has “a latent fire which hints at itself, and which could, but chooses not to burst into flame” (Baudelaire). Why does Liz keep the flame cool, keep it controlled, keep it from burning? In Tony’s other cameo, he gives us the answer: Twins are a cosmic error. “You’re supposed to be born on the opposite side of the earth. Sometimes one chases the other and winds up in the wrong place. I’m guessing you chased your brother because you knew he needed you. You’re stuck in the wrong place.” Or, alternately phrased: “Warm air above land expands and rises, and heavier, cooler air rushes in to take its place, creating wind.” Define yourself by balancing out another, you end up off-kilter whenever the other’s not around. Liz throws on a wetsuit that night, goes out with dead, walks headfirst and unflinching into the waves, floats on her back in the great abyss. Frog-kicking across the galaxy, a sea of stars. Even Long Beach looks like a Milky Way blur of distant life from where they drift.

Where Lodge 49’s characters live in a world of tides and pools and bottomless tabs, Chinatown casts Los Angeles as desert, spiritually desiccated of its vitality. There is a massive ocean; Dud just happens to be exiled from it, cast out by a serpent whose bite-wound stays with him like stigmata. Dud just needs to get back in the water, in the flow; its energies and currents are waiting for him, if he can regain his sense of balance to surf them.

*

Pynchon’s characters are always at the edge of discovery, as if walking the shore of the great ocean… But in the open sea of indeterminate chaos is only a drowning. Last time:

“The basic dichotomy of [Moby Dick], the sea and the land, is the way [Melville] expresses on the one hand the indeterminate chaos, and on the other hand the need for something solid, something you can take a stand on and count on…” (Hubert Dreyfus)

“Primitive Peacemakers pt 3: Water Metaphors”

Land [in the novel] is marked (“landmarked,” signposted, that “turnpiked earth”); sea is unmarked, and “permits no records.” Static versus dynamic, stable versus chaotic, solid versus liquid, fixed versus shifting. The sea is therefore uninhabitable; habitability requires regularity, and so human niche construction creates reliable recurrence that scaffolds and supports its habits. (We refer to stability as solid ground beneath our feet, in contrast to “oceans of complexity” and “seas of information.” )

Liz, Dud’s twin sister in Lodge 49, jumps off a company cruise into this great open ocean, and it nearly swallow her. Her mother swam at night in this endless Pacific, and her father drowned in it. The television series, like teen beach-rat phenom Outer Banks, participates in the Drowned Father archetype. Classically, this means the father’s body is never found; the son holds out some hope of finding or saving or reconstituting his father; in the process of searching, he himself becomes the father. Here, Dud’s under no delusion that Dad might still kickin’ it on a Caribbean island somewhere, evading loan sharks and the IRS. But he’s single-minded in his effort to adopt a replacement father, Ernie the latest in a string, which is sort of a way to postpone growing up, and sort of a way to learn how to grow up. Later in S1, the much-pursued “Captain” of the Long Beach development game is revealed to be a fictional character—a legal construct, a public relations image, played by an alcoholic (the perfectly cast B-movie star Bruce Campbell). While Dud pursues Ernie, Ernie pursues the Captain—who turns out to be yet another drowned father, boozed-out in a kiddie pool. (Which is also an oasis in the desert.) Then, once Ernie’s taken over as father figure to Dud, he suffers a navel-gazing crisis of faith, ends up drowning in depression and lost hope.

Andy Clark, in his predictive processing magnum opus, Surfing Uncertainty, uses the surfing metaphor to describe human cognition, and there’s something powerful in its metaphor of a trained, sub-verbal, gut-and-feel calibration of the body in response to “the wave,” the causal delta we all surf, a ripple of change and disruption and chaos—and therefore energy—that if we angle ourselves to just right, is a source of powerful forward momentum, and if we angle ourselves wrong, will wipe us out in its spume…

Ernie’s last name, Fontaine, is a near-match for “Fountain”;30 the Captain’s wife is a marine biologist; and there’s a recurrent “mother sea” motif which is compelling because it’s not just mythically but scientifically true; our Darwinian origins lie in the water. The healthy ranges of saline content and mineral composition in our blood and bodies map to those of ancient oceans, what our single-celled ancestors would encounter from “bathing” in the hydrosphere, being one with their ambient surrounds. In our migration to land, we took the sea inside us, use our skins as protective membrane to seal the sea in, replenishing our fluids and minerals through foraging. Eggs and wombs are just miniature oceans, warm lagoons. We are all mere temporary sacs of water that return, one day, to the hydrocycle. Processes of water individuation and deindividuation, cycling through time.

I lost nine shy mimosa pudicas to dehydration last week. Half the crop, or what was left—I’d begun with 28 seeds, soaked in water to help the germination process, and many never sprouted.

Continued & concluded in Part 2.

End Notes

- This comes immediately after Dud gives a schpiel about the supposedly utopian lifestyle of the American Indians who lived in California before colonialism: “no war, no hassle,” just three-thousand years of fishing, surfing, hanging at the beach. Dud recounts his previous, pre-snake bite life in similar terms, earlier in the episode. Myths of personal fall, social fall, and religious fall are frequently intertwined. ↩︎

- It is also a very different structure of story: detective stories, as Chesterton argues, are traditionally geared around the hero’s transformation of complexity to simplicity, concluding when he discovers an Occam’s razor that fully explains what was previously a mess or tangle. Any misunderstanding or confusion is temporary, meant only “as a dark outline of cloud to bring out the brightness of that instant of intelligibility.” In Lodge 49 and Lot 49, this narrative-arc toward illuminating clarity remains only as a sought-after fantasy, never realized. Oedipa’s main moments of illumination are described as “blinding,” an overwhelm that prevents rather than enables vision ↩︎

- “If you’re not working on a project, your thoughts will eat you up,” one Lodge member—recently laid off—confides. See also James Carse on infinite games. ↩︎

- Arriving in the Golden State, Michel Foucault would remark that “Europe is far behind California,” and tell a Claremont undergrad “You do not need to read my books” (Foucault in California). Simeon Wade, his trip guide at Artists Palette, saw Foucault as “the Parisian spokesman of the ‘Molecular Revolution’” of Californian LSD. ↩︎

- Of course, Silicon Valley’s changed a lot since the golden olden days, startups slowly slipping into simulacra (see Alex Danko’s “Are Founders Allowed To Lie?“). But the West Coast engineering mindset still defines itself in opposition to the social and language games of East Coast finance and art, as having contact with an intrinsic reality that stretches beyond bourgeois social construction. ↩︎

- “I want to break out—to leave this cycle of infection and death,” Blicero tells Gottfried in Gravity’s Rainbow. But on the other side is death. On the other side is always death. People overdose trying to break through on heroin, trying to “chase the dragon.” The culmination of psychedelic experience is termed “ego death.” The climax of eschatological religions is mass extinction; the logical endpoint of prophetic cults is mass suicide. Noah Cross v. Jake Gittes in Chinatown is a show-down between mask and unmasker, illusionist and detective; Gittes gets the truth, or part of it, but it costs him in blood. ↩︎

- Lot 49: “The act of metaphor then was a thrust at truth and a lie, depending on where you were: inside, safe, or outside lost.” Depending on whether you are represented, whether you are excess or “subaltern.” ↩︎

- This makes Pynchon’s work “comic,” in the sense of tragedy and comedy outlined by Hotel Concierge in the lost masterpiece “Distance & Closeness.” Tragedy is defined by its fatedness: a set of premises are laid out at the start, and the plot moves mechanically to their conclusion. Even a superficially “happy” ending can be tragic insofar as it presents a closed world. Comedy, on the other hand, sees its initial premises actively subverted, often by wilderness magic—that is, by the extra-rational and supernatural that lies outside the city gate, out beyond the mapped and gridded order of things. Of particular interest to Pynchon scholarship is the conceptualization of comedy and tragedy as high entropy and low entropy, respectively (in the information-theoretic sense of the term). ↩︎

- See S1E8: Dud and Ernie, disenchanted of a get-rich-quick scheme, drink lager and stare into the mirror, depressed. Rather than breaking through, they’re stuck with their own reflections. Tangentially, Liz and Oedipa both break mirrors, early in their journeys, and crack some version of the “seven years bad luck joke,” but we can also understand these moments as dissolutions of their identities, a breaking of bonds to allow re-annealing. ↩︎

- Perhaps we’re naturally uncomfortable in these in-between zones, always wanting to resolve things one way or the other. See e.g. Connie and Ernie, their interminable bargaining and re-negotiating over the terms of their relationship, so that it sucks up all their time together, banishes all their love to the margins. Alternatively, Chesterton suggests that this single-mindedness is a particular morbidity of the modern intelligentsia. “The ordinary man… has always cared more for truth than for consistency. If he saw two truths that seemed to contradict each other, he would take the two truths and the contradiction along with them. His spiritual sight is stereoscopic, like his physical sight: he sees two different pictures at once and yet sees all the better for that” (Orthodoxy). ↩︎

- Nick Freeman, in “Chesterton, Machen and the Invisible City,” relates the historical precedent for this sort of urban description in 19th century detective novels:

The official centre of the world after the establishment of the Greenwich Meridian in 1884, London was a multivalent symbol, standing for Empire, Nation, Tradition, History, Ingenuity and Inhumanity, depending upon the ideological perspective of those seeking to deploy its symbolic associations. Within it lurked millions of smaller symbols, from individual buildings or statues to pub-signs and street names, which could confuse and disorient those untutored in deciphering their significance. In Bleak House (1853), the illiterate crossing-sweeper and hapless semiotician, Jo, is ‘unfamiliar with the shapes, and in utter darkness as to the meaning, of those mysterious symbols, so abundant over the shops, and at the corners of streets’ and Dickens’ narrator ventriloquizes his incomprehension and bewilderment. ‘[W]hat does it all mean’, he asks, ‘and if it means anything to anybody, how comes it that it means nothing to me?’ …Which is worse, asks Kelly Hurley, ‘London as a chaosmos—a space of meaningless noise, activity, sensation in which narratives indiscriminately crowd one another and no one narrative has any more significance than the next’ or ‘the paranoid fantasy of a London whose seeming indifferentiation masks a network of deeply-laid and infernal designs’?

Could Pynchon have read Chesterton, and been informed by his treatment? For G.K. wrote of “the poetry of London” as “a chaos” of intentional messages and deliberate symbols, “every brick” a “hieroglyph,” “every slate on the roof… as educational a document as if it were a slate covered with addition and subtraction sums.” All these symbols contribute to the great, unreachable mystery of the city, pointed at by “every twist of the road,” signaled by “every fantastic skyline of chimney-pots.” The urban detective, to Chesterton, was a distinctly modern hero, tracing clues in this vast space of hidden meaning, of hard-to-read messages and hard-to-square facts. He also helped assert an urban romance that helped put readers in the habit of “looking imaginatively” at their city. Or perhaps Pynchon was indebted to Doyle himself, who once had a hero complain that “There is not a vein upon a leaf, not a scratch upon a pebble, not a torn word on a scrap of paper, without a message for me, and I am in despair because I cannot read the meaning here.”

To say that the detective’s meaning quest is also an act of world-creation is not to deny the existence of objective, subject-independent patterns in the world, but to emphasize the detective’s degrees of freedom in choosing which patterns to follow, and why, and for whom. This choice can be undertaken in full consciousness or not; either way, a decision is made. The hero-as-enchanter is ultimately a curator of the “chaosmos” of life; from an infinitely detailed sensory array, he selects certain details to treat as load-bearing symbols, and then selectively interprets, pursues, and assemblages these symbols into narrative structure. If the detective is a literary theorist, a professional interpreter and hermeneuticist, then the detective-as-enchanter is a return-maximizing critic: “There are no truths, only instruments, echoing Bloom’s ‘what is it good for, what can I do with it, what can it do for me, what can I make it mean?’” ↩︎ - If Pynchon sounds like a post-rationalist, it’s in part because he came up within a cybernetic control paradigm, meaningfully analogous for our purposes to LessWrong-style rationalism, in terms of technocratic ideology and quantitative method. ↩︎

- “But a pattern can stretch for ever and still be a small pattern,” Chesterton continues in a nod to ontological pluralism. ↩︎

- A story is essentially a theory of actions and payouts: a character does something, and then something happens (to or for him). It is a model of the world in temporal patterns of cause and effects. Hence the role of storytelling in religion, political propaganda, and community organizing: everyone sits around the fire and gets synced up to a framework for thinking and doing. Cynically, you sell people narratives, and their concomitant payoff structures, so that they behave a certain way (“rationally,” that is, out of self-interest) and specifically, behave the way you want them to. Hence all the virgin allocations in the afterlife. Hence the piece of British-nationalist propaganda Oedipa watches in her motel, early in Lot 49, where our patriotic father, son, and holy St. Bernard all receive beautiful women as prizes for their patriotism: a “leggy ringletted nymphet” for the son, “an English missionary nurse with a nice build on her” for dad, and “even a female sheepdog” for the St. Bernard. Hence Connie (“con-y”), Ernie’s old lover in Lodge 49, which Larry—a walking conman him—calls “Ernie’s gift from the Lodge,” a little something for loyalty and sticking around. We’ll follow any guru who can plausibly claim to produce value; we care less about metaphysics (which are, by definition, irrelevant to our worldly aims) and more about the pragmatics of local returns. Much is made of studies where rates get rote-conditioned into Pavlovian routines through cocaine—but storytelling (epitomized in centralized, commercial form by the Tube, archnemesis of one Thomas Pynchon) shows us where rats get their cocaine fixes, and then asks the viewer, “Et tu?” (Lot 49’s Mr. Thoth, named for the Egyptian god of writing and communication, says of the TV: “It come into your dreams, you know. Filthy machine”—and we are reminded of how lifestyle fantasies are sold at Mucho’s used car lot, a leveraging of mimetic models and identitarian aspiration.)

The Internet, meanwhile, democratizes the process of mass-audience storytelling; see the recent bottom-up meme magic of GameStop and Vibe Shift. Dimes’s Honor Levy, interviewed on Ket Patrol, confesses: “I believe the Internet can summon demons. Chaos magic is not something to be messed with, and it’s kinda scary.” Or see post-rat pseudanon Allgebrah: “The web connects all the minds and a pluralistic, often split-brained shared mindspace emerges. Every sentence modifies someone’s personal reality, our every word has consequences… Meme magic is supercharged pragmatics.”

Where the social magic comes in is in the subtle manipulation of symbols and social capital so as the change the payout of games. When we choose which six-pack to bring to the party, or what cut of jeans to buy, or how much to tip for service, we are guided by that communicative consideration, “What will my choice say about me to others?” Kevin Simler, “Ads Don’t Work That Way,” dismisses all the conspiratorial, Inception-style theories of ads as social conditioning, and suggests something more modest—like an excluded middle between theories of man as rational animal and independent actor, and theories of man as automaton, helplessly swayed and controlled in decision-making by forces outside of his control:

Cultural imprinting is the mechanism whereby an ad, rather than trying to change our minds individually, instead changes the landscape of cultural meanings — which in turn changes how we are perceived by others when we use a product. Whether you drink Corona or Heineken or Budweiser “says” something about you. But you aren’t in control of that message; it just sits there, out in the world, having been imprinted on the broader culture by an ad campaign. It’s then up to you to decide whether you want to align yourself with it. Do you want to be seen as a “chill” person? Then bring Corona to a party.

And this is how default tipping, and any of the effective “nudge” and “priming” effects, really work. They work by changing the structure of game payouts, they work by intervening on common knowledge. If we tip to be polite, and 20% is set as a default tipping option on a swipe-screen, then it becomes impolite to give a 15% tip, whereas a 10% default implies that 15% would be generous. Tippers aren’t irrational for changing their behavior in response to default. Rather, the defaults change the social meanings and connotations of different actions, i.e., alter the payout-structure of the game. Tippers—simultaneously rational and manipulated, free to choose and powerless to determine payouts—update their strategies accordingly. And the entire thing is a sort of social magic because it occurs implicitly, and non-consensually, rather than making an explicit bid which individuals can accept or reject.

The tendency of stories to make themselves true has been called many names, historically; most recently, it is called “meme magic” or (via the CCRU) “hyperstition.” One occult foundation for Lynx-like occult orders is Rosicrucianism, referenced a few times over the seasons, and it’s thematically relevant that Rosicrucianism itself is a hyperstitional order, that is, a myth made real—originating in a series of most likely fictional messianic manifestos in the 17th century, which—as is seen commonly today with media coverage—created the very phenomenon it claimed to report on. Dud explicitly contrasts the Order of the Lynx with Rosicrucianism, using the latter’s fantasy as a point of contrast with the Lynxean “reality”—one more narrative move, one more unconscious rhetorical strategy, the product of an enchanting habitus. ↩︎ - “Colored beads” is a quote from Emerson, addressed at length in “Primitive Peacemakers.” ↩︎

- When Oedipa comes across the color white in Lot 49, it is described as blinding overwhelm: “All she could think of was to put on her shades for all this light, and wait for somebody to rescue her.” Moments of revelation are compared to epileptic seizures, which she exits amnesiac, “left with only compiled memories of clues, announcements, intimations, but never the central truth itself, which must somehow each time be too bright for her memory to hold, which must always blaze out, destroying its own message irreversibly, leaving an overexposed blank when the ordinary world came back.” ↩︎

- Ioan Petru Culianu, Eros and Magic in the Renaissance. ↩︎

- Pynchon, who avidly read Kerouac in his youth, would have recognized enthusiasm as the primary source of charisma for On The Road’s Dean Moriarty. ↩︎

- Richard Wasson, “Notes on a New Sensibility”; Partisan Review 1969. ↩︎

- The lynx—as mentioned explicitly in an early episode of Lodge 49—is historically a symbol of powerful vision. ↩︎

- This sort of pluralistic potential of perception is what Dud nods toward, in his remarks at his father’s funeral:

The truly great alchemists know how to control matter and energy; it allows them to access eternity, like they’re sitting above the maze, no past or future, just the eternal moment of paradise. Everything that we think is gone is still here in front of us. That’s what alchemy teaches us to do, to access those hidden worlds: countless heavens, countless suns.

Countless heavens, countless suns. The hidden lifeworlds entered by trained vision. Paradise may be a myth, but those who fail to believe in it, on this show—like Gloria and Liz, like Connie—end up walking dead, imprisoned in madness by their own reductive, depressive ontologies. ↩︎ - Mendelson, “The Sacred, The Profane, & The Crying of Lot 49” ↩︎

- Janet, CEO of Orbis, tech visionary and wunderkind, offers another reference point in the prophetic leader model; she’s defined by her deep commitment to the bit, her self-aware performance of personality, her use of jargon as mystification, and her fraudulent corporate practices—her literal and metaphorical accumulation of debt. Out at sea, she tells Liz, “I just run as fast as I can and hope it doesn’t all fall apart.” ↩︎

- Actor Wyatt Russell on his character. ↩︎

- You get the same dynamic in startups: charismatic, prophet-founders who massively overpromise to investors, securing seed funding but forcing engineering to rack up a pile of tech debt whose compound interest keeps mounting. Sooner or later, the wolf’s at the door: better have your shit together or else. There’s a reason that engineering departments, attempting to counter this trend, have everywhere adopted the motto of “Underpromise, overdeliver.” It’s a torque thing. ↩︎

- It’s the same with all the Lodge’s rites and ceremonies: “There’s a solemn oath, and then we will begin to entrust you with the mysteries.” Dud: “Entrusted with the mysteries… That’s all I ever wanted.” Ernie: “We usually order a pizza or something afterwards.” ↩︎

- “The rhinoceros is a fascinating animal. All this beautiful stuff, right here in front of us. Screw unicorns, man,” Ernie quips. ↩︎

- Likely a spiritual influence on Lodge 49, the titular Henry Fool is our stranger-walks-into-town enchanter, who “wakes up” (i.e. sets a spell upon) the film’s hero Simon Grim, inspiring Grim to write poetry. ↩︎

- Similar unlikely co-occurrences abound, and the word “coincidence” is a minor leitmotif for Lodge: used to describe Dud’s snakebite, Dud’s temp job for Captain, and El Confidente’s painted prophecies. Roger Callois, The Writing of Stones (1970), in what passes for Pynchon theory:

This sort of coincidence is not an illusion; it is a warning, a signal. It bears witness to the fact that the tissue of the universe is continuous, and that in the vast labyrinth of the world there is no point where apparently incompatible paths, from antipodes much farther apart than those of geography, may not intersect in some common stela, bearing the same symbols and commemorating unfathomable yet complementary pieties. ↩︎ - h/t Reddit user u/Gleanings. ↩︎

Leave a comment