Last time, on Suspended Reason….

Prophetic revelation involves for both the prophet himself and for his followers… a unified view of the world derived from a consciously integrated and meaningful attitude toward life. To the prophet, both the life of man and the world, both social and cosmic events, have a certain systematic and coherent meaning. To this measning the conduct of mankind must be oriented if it is to bring salvation, for only in relation to this meaning does life obtain a unified and significant pattern.

Max Weber, emphasis added

- S2E1, “All Circles Vanish”

- Narrative Collapse

- The Prophet

- The Faith of the Prophet

- Prospero’s Lysergic Island

- Portals, Postmodernism & the True World

- Afterword

- End Notes

S2E1, “All Circles Vanish”

We closed the first season with Dud’s shark attack, after his first trip past the break—flickering in and out of consciousness, blood diffusing into brine. Now, our first shot is of a shark-tooth necklace, a token of the predator conquered, the dragon slain. The camera zooms out; we see it’s Dud’s neck from which the amulet hangs. On his face he sports a wide smile; over his heart, the family crest: “Dudley & Sons” emblazoned on an aquamarine t-shirt next to palm tree graphics. “Soñar el sueño imposible,” he says. “The impossible dream,” Ernie sing-songs back to him, decked out in a full Mariachi suit, grin-plastered; they’re seated in the cabin of a private plane. “We did it man”; they shake hands. They’re as high as it gets, as high as they’ve ever been. The last time we saw them like this was when Captain cut ‘em in on a million-dollar oil deal. Or, you know. When they thought he had.

A curtain at the front of the plane is cast aside by a balding, gray-mustached man in a double-breasted peacoat, a backstage Oz, announcing gravely: “Gentlemen, the dream is over.” We don’t know it yet, but this man is the engine of their adventure. When Dud and Ernie’s faith failed, in the long hangover of the Orbis rollercoaster, it was his amphetamine-energized enthusiasm that rallied them back into questing. “Captain.” And he’s pressed the wrong cockpit controls, and the engine’s on fire, and they’ll need to jump. “You said you could fly a plane,” Dud answers in shock. “In my heart, I thought I could.” Piloting is an ancient metaphor, about reading the sea, the stream, the air current; about responding to these natural flows of energy to get somewhere; about keeping the vessel seaworthy and afloat, keeping it airborne and intact. To be piloted is an act of trust and necessity, your fate in another man’s hands. The vessel can wash up on the rocks, or crash-land at sea, can sink to the ocean floor and hit rock bottom.

Traditionally—to solve alignment problems—the captain goes down with his ship, or at least stays til everyone else is done deboarding. But this pilot—like so many who seek and relish the job—is guided by ego. (Ego and pride being the principle flaws of the magician.) So out he jumps, with one of the parachutes. Now there’s just one chute remaining; the only way Ernie and Dud are surviving the crash is by strapping in together, their fates intertwined. They jump.

The scene cuts; the chronology winds back six weeks. This is where the season will end—everything we’re about to see will work up to it—but it makes sense to put the scene here, at the beginning, because it gets us in the mindset of a crash. The crash that just happened, the crash that ended S1. Everyone’s crashing out this episode; only some of them know it yet. The seasons are structured as a working up to enchantment, followed by disenchantment. “If you want to break someone completely, you get their hopes up first.”1 Ernie’s burnt out because he’s become disillusioned in both the faith-structures he’s a part of—the Lodge, yes, having seen behind the scenes and profanized the sacred, witnessing the Sovereign Protector’s descent into madness and fraudulent books, a Mexican treasure hunt to nowhere—but also at his day-job, where Brian Doyle-Murray holds down the ship as a backwater, blue-collar captain, with his Hawaiian shirts and Keats quotes. And then there’s the Orbis deal: he thought he’d finally found the eye of the system, the center of the maze, and it turned out to be one more legal construct, one more paper entity, one more mask, a “shell within a shell,” just one more obfuscation.

Dud, meanwhile, is having prophetic dreams and visions, of astral light and things to come and divine contact. Even in the hospital, recovering from the shark attack, he’s irrepressibly optimistic—glowing, irradiant, full of astral light. With his sun-bleached hair, he’s a foil to brunette sister Liz, black-hole of depressive darkness, who mocks Dud for his naivete and hermeneutic charity. It’s not surprising she’s disenchanted, either—her day job’s at a chain called Shamrocks, best described as “Hooters meets an Irish bar,” and whose business of flesh profanes its sacred symbolic namesake, a Celtic trefoil standing for the Holy Trinity. But purify your thoughts, you purify your world, alchemy tells us; is there some Law of Attraction at play, might a profane nature attract a profane lifestyle?

It’s true that Liz is more grounded, “realistic”—but this identification runs cover for a deeper detachment and nihilism. Dud’s never worried, and always sees the best in situations or people. Liz is never satisfied, always suspicious, and only sees the risk. But Dud also needs handlers to (quite literally) keep him alive. One of them is Sister Liz. Another is Ernie. This is a common pattern of social solution for high-charisma, impassioned individuals: they need to be surrounded by more stable and even-keeled personalities, who will buoy them in times of depression, and keep them tethered to Planet Earth during their manic rocket-fuel highs. And sometimes a handler’s reality checks weighs down too heavy. They’re too sober. They reject the call of adventure. “We can go up to the roof, see the stars,” Dud silver-linings when Liz has to pawn her flat-screen. “There are no stars in Long Beach,” she retorts.

Liz punctures and disenchants every romance she comes across.2 That’s romance in both senses of the term; falling in love is a process of mutual enchantment. And every time Liz risks falling into a fairy tale, she pops the bubble preemptively, the ego-salve of a cynic who’s terrified the illusion won’t last.3 “If you want to break someone completely, you get their hopes up first.” If you never hope, you’re never suckered, you’re never broken. She refuses every enchanted call to adventure, and has long ago given up on dreams, as another fantasy removed from the grim realities of everyday misery. All she thinks about is her crushing debt. (“There’s no way out,” she screams at a honking car behind her, gridlocked in traffic.) She’s constantly getting in conceptualization wars, battling to live inside the least-romantic framework at every possible moment: “How may I assist you in your healing process?” Blaise asks when she enters his apothecary. “I just want to get high,” she retorts.” Blaise, gracefully returning: “That is healing! Are these items recreational? Of course, insofar as they allow us to re-create ourselves, get back in touch with our subconscious. Modern man lives on the surface—” Liz doesn’t let him finish, cuts only to the price, practicing that ancient, economic form of disenchantment. She is the scrawled graffiti on the Orbis redevelopment billboards, answering “Is there another way to live?” with a definitive “No.” Ernie has similar patterns. “There’s no secrets, no hidden worlds out there,” he tells Dud; a few hours later, they crash through the wall of an hermetically sealed alchemist’s room, hidden behind the Lodge’s Sentinel Suite.

Dud, our Holy Fool, enchants everything he touches; he’ll step off a cliff because he’s busy starting at the stars; he embodies an eternally optimistic, energized and eager belief. (See e.g. the gorgeous golden Volkswagen he drives, which lacks both seatbelts and airbags.) “I kinda feel like I’m floating on air,” Dud tells surfer-girl Alice; while Dud speaks, in the backdrop, we can see the enforcer for local loan-shark Burt, patiently waiting for him. Liz is terrified that Dud will get killed, or kill himself, the way Dad went. That the compound interest of living inside a fantasy will keep on piling, til it buries him alive.

We’re tempted to ask, “Who’s right? Which view is truer, which position is better calibrated?” The way we might, like Oedipa Maas, wonder whether she’s in the orbiting of a true paranoia, or a real Tristero; whether there is transcendent meaning, or only the earth. Our error is ignoring the excluded middle, because neither Liz nor Dud embody a working solution. Dud is always at risk of dying, and Liz is already in the underworld, already Thanatoid—floating across the Shamrocks floor in a half-conscious trance, wanting to die for real. Both are “walking dead.” As twins, they’ve taken up opposite polarities, a kind of familial niche-finding, the burden of her responsibility to “reality” made all the heavier by a missing mother, so it was just her, counterbalancing her brother and her father, outnumbered. They subsidize each other, co-dependent, like all members of a group or family. This is how they talk to each other: “Do you understand how delusional you are?” “Do you understand how miserable you are?” “You get to live in a nice little bubble and I get to pay for it.” “You’re afraid of the light; you live in a witch cave.” Each lives together, in the same “world,” and yet each lives in a radically different mood, different atmosphere, different umwelt. “The reality is in this head. Mine. I’m the projector at the planetarium,” a theater director tells Oedipa, in response to her treasure-hunting for play’s original, “authoritative,” underlying text.

Narrative Collapse

Knew this game was won by outlasting everyone, but forgot to account for how lonely it gets when the numbers really dwindle. Sometimes—usually—it seems that the ones who stick it out longest are the unreasonable ones, the deluded ones, the ones who refuse to get real, who ignore the signs others would follow, and find their own system for divining. Sometimes it’s the people who live in their imaginations, and sometimes it’s the narcissists, and sometimes it’s the ones who will to believe.

Reality always seems to catch up to Ernie. Larry and Connie were his enchanters; see e.g. Ernie always trying and failing to start his car battery, Larry his power source, giving him a jump. When he looks at Connie he has “stars” in his eyes.4 By the end of S1 he’s lost both. Oh, Ernie can get carried away for a little while, sure, in Dud’s mythologies—but mostly he sees his squire as a Quixote. In S1, he gets caught up in his own, quasi-secular hero’s journey pursuit of the Captain—a panacea or “grail” quest5 in its own right; “I’m tired of the nickel and dime,” he tells his boss—he’s after gold. He’s convinced he’s figured it all out, the whole plan, the whole system—can’t they see it? All he receives is a sobering warning from his boss that he’s “chasing shadows,” that “these big projects just never pan out,” L. Marvin Metz6 narrating, “…glittering like fool’s gold.” Best not to think about it; why pop the top-down bubble with bottom-up data? Spirits are high, why second-guess? Why have a lawyer review the contract? Desperate not to jinx it; unwilling to speak his greatest hopes out loud. Eventually the Captain quest turns out a financial dead-end, one more fraud in a series of frauds. Ernie learns the lesson, and crashes back to Planet Earth. “I only saw what I wanted to see, the whole time.”

This is the shape of a parabola7; this is the arc of gravity’s rainbow. The rocket gets you enough thrust to get off the ground—but it either sputters out before breaking free of gravity, plunging back dangerously to the ground, or else it breaks throug

Somehow, it never seems to catch up to Dud. Dud’s a water person, like his sister. He’s fluid; he floats; he “rolls with the punches.” Somehow, he never seems to wipe out on the wave, and when he does wipe out, he just gets back up, paddles past the break again. When the belief structure starts wavering, and you start analyzing it all with that verbal voice of sober “reasonableness” we all carry, the structure ends up crashing all around you. Maybe you’re quick to notice a wiggle, but you re-stabilize by orienting your entire self towards an ideal vision of stability—not by cathexing on the disruption until it amplifies and tosses you off the board. The dream? When that wiggle-noticing, ideal-orienting, becomes so automatic it’s all just perpetual flow-state.

Instead, the sound of crows are heard on your rooftop each morning when you wake. You take to carrying a pellet gun, to fighting death with death. But now the worst part is the blood on your hands, the traces and marks of your history that condemn you. That lead you to double down, push yourself past redemption. Moods bleed between people; your own pain is doubled by inflicting it on others, a pyramid scheme of suffering. Heaven isn’t a place you can get to, but believing you can seems to make your world incrementally more Heaven-like, while believing you can’t makes it increasingly Hellish.

You start breaking down when your narratives start breaking down. Others notice the cracks and try to reach out, but you rebuff them with more confidence fronts. The manic upswing is always answered by a depressive downswing, an endless oscillating sine wave, and what comes first, the disillusionment, or the depression? Neither: they’re the same phenomenon. You start “flying,”8 way above ground, and at some point you realize there’s nothing supporting you, and you arc towards the earth, the momentum taking you into the underworld. Peak to trough.

Finally you reach the bottom. Without any answers, or working solutions, every grifting promise of panacea tempts you into its structure of meaning, its chase, its thrill of pursuit. “Captain has all the answers. You need to go to the desert. You need to find him.” Or you’re on a boat at sea, nowhere to go, but you pitch over the side anyway—into the shimmering water that promises everything, nothing, totality.

Blaise, descending into madness, provides our second negative example. Like Dud, he is fiery and faithful; his belief in the other side, in breaking through, sustains him. But he spirals out, starts threatening friends with physical violence, is admitted to an inpatient facility, where he swears off all the alchemical nonsense, all the dream-chasing. But it wasn’t dreaming that got him there; it was his single-minded commitment, and the way he went about securing it. Alchemy lends itself to this sort of manic, self-destructive devotion, to the making of poor Pareto trades, because it promises something like paradise. Blaise’s spiral is accompanied by a descent into asociality—he walls himself off, self-isolates, starts wielding a weapon. He was so strong once: Can we remember him scorning Avery’s manipulative advance, disavowing the pursuit of gold: “9I’m a doctor, a healer.” Now he’s aiming nail-guns at his Lodge Brothers. At some point, the pursuit of a single set of answers came to usurp his ecology of practice. He stops caring what effect his search has, what byproducts it creates in the world he inhabits. Like Oedipa, worn down by Chapter 5, the quest has robbed him of more energy than it’s given back; the philosopher’s stone, with its promise of immortality, has become a memetic parasite, sucking his vitality. All he wants is “the” truth—tantalizing, on the edge of understanding—and this is precisely why truth is denied him: he has tuned himself out to all its other frequencies.

The Prophet

And who is our prophet, who enchants the world of men? Who is this hero-as-enchanter?

To Weber, the prophet stood in stark contrast to the bureaucrat-priest, who “lays claim to authority by virtue of his service” within a tradition or institution. The prophet is always an individual, an outsider, who succeeds through charisma and personal revelation. The bureaucratic dispensation of the priestly make it “no accident that almost no prophets have emerged from [that] class.” In Lodge, that’s Jocelyn, heathen priest and pencil-pusher, a “wizard of demystification.” By necessity, the prophet is a force of disruption, hailing from the alternate order of the sacred, standing out unique amidst a profane world. He is is a comic surprise, something new on the scene; his arrival “wakes up” the Lodge, as Blaise puts it—and wakes up Larry, and Ernie too. (Though they awaken, specifically, to a dream-like, Faërian spell.) He is an excess, who by virtue of being undescribed by the system, remains uncaptured by the system, and is able to disrupt it towards some new equilibrium. “I spent fifty years pouring concrete, drinking at the Lodge,” Larry says. “Now I see there’s so much more.” Liz is determined to believe that there isn’t, and couldn’t be, anything “more.” She opposed to the concept, a priori. And Ernie, in his conservative spells, feels the same. They live imprisoned in the tower of their own barren imaginations.10

The prophet and the magician alike trade in divination, oracle, and dream interpretation.11 The prophet, like the inter-subjective magician, is a species of actor—typically, an actor who truly believes in his message and act, and is made more powerful (take on an aura12) for it. Facework (“acting,” our everyday performance and presentation of self) is a form of magic, of constant subtle communication and the Goffmanian management of impressions. Lawyering and acting are extensively compared in Lot 49 because both are practices of strategic framing and motivated conceptualization, boosted by the charisma of facework and confidence (from which we derive the “confidence game”). There are many ways a story can be told, many ways that a set of clues can be assembled. Which do we choose, and why? A skilled framing performance takes all the controversy and hides it away in the background, as the “natural facts” of its own premises, as a definition of the situation, rather than an explicit move or bid in the language game.13 This is the magic of metaphor: it suggests a frame, suggests a string of entailments that may or may not apply. Choose a different metaphor, get a different prescription… Adopt a different framing, change your life…

To Lodge 49, the prophet authors a sense of fatedness and amor fati, while almost paradoxically being driven by a desire to break through and transcend. (Elsewhere, a former Sovereign Protector daydreams to her diary about awakening from history.)

He is a salesman (Jesus Christ is “the best salesman of all time,” Captain tells us) and often the quality of his goods are questionable. A master of surfaces, he is sometimes less than scrupulous about the state of transmissions. His enchantment is a form of propaganda. We see one incarnation of the salesman-prophet motif in corporate exec Janet and her jargon-wielding disciples, who tell in-training execs to “eat, drink, shoot, or snort” company commandments, which were received by Janet Moses-like upon the mountain.

He is, in some sense, a fraud—a word used at varying times by Blaise (both as self-description, and in accusation of Avery), Ernie (describing Larry and the Captain), the Captain (describing himself), Dud (describing Scott’s Sovereign Protector usurpation), and Wallace Smith (describing himself). He is a con artist and a scammer, the head of a pyramid scheme (like Oedipa’s tupperware party or Lenore’s Fydro).

He spends his time alternating between leadership positions and mental health centers (treating his manic depression). With the mania comes magic; with the depression, a crippling crisis of confidence. There are ebbs and flows to faith; every belief, every model, is a sort of prediction, and when the predictions pay off, the faith is renewed, and when it fails, we’re tempted to ditch the framework in its entirety. One moment Blaise is warning against miracles; then a miracle occurs—the (apparent) exorcism of a parasite through alchemical teachings, and he’s back on the saddle, a holy knight and Quixote.14 These demonstrations are equally necessary in maintaining the fate of a prophet’s followers, who in joining the prophet in his questing, are like Sancho Panza more concerned with the byproducts of that quest, than the metaphysical claims and holy grail that motivate it. (When does Captain win back the flagging, strung-along Ernie? When their trip to a cock fight bags ‘em $3500 a head.)

He is a man who has suffered catastrophe, who has been orphaned and cast out of the garden, cast out of the waves he once gaily surfed. Who now searches for a way home, not so much discovering that home as at the end of a journey, but creating that home through the act of journeying itself.

The Faith of the Prophet

“Would you be able,” my wife asked, “to fix your attention on what The Tibetan Book of the Dead calls the Clear Light?”

I was doubtful.

“Would it keep the evil away, if you could hold it? Or would you not be able to hold it?”

I considered the question for some time. “Perhaps,” I answered at last, “perhaps I could—but only if there were somebody there to tell me about the Clear Light. One couldn’t do it by oneself. That’s the point, I suppose, of the Tibetan ritual—somebody sitting there all the time and telling you what’s what.”

Huxley, Doors of Perception

And the world will be better for this

That one man, scorned and covered with scars

Still strove with his last ounce of courage

To reach the unreachable star

Man of La Mancha

The role of the hero-as-enchanter is to provide faith, which he secures through charismatic authority and the performance of miracles. But this provisioning requires the enchanter to have faith in turn; “the preliminary faith of the performers is the condition essential to success of the magic act.”15 But who supplies the hero-as-enchanter with this inner faith? Who supports and reinforces it? When it collapses, why does it collapse?

We see an answer in Prospero’s closing monologue of The Tempest.16 It is as much in the audience as the magician, where magic lies. It is their reception which feeds back into his performance, their belief sustaining his belief, his belief sustaining the enchanting scaffold.

Emotional energy, Collins writes in The Sociology of Philosophies, “charges up individuals like an electric battery, giving them a corresponding degree of enthusiasm toward ritually created symbolic goals,” both within the space of group interaction, and also, if the magic is strong, outside the presence of the enchanter. And this emotional energy flows both ways, in a circuit. “Cringe,” for instance, is the subjective experience of observing a failed attempt at creating sacred experience, a failed attempt at magic (Perry, “Cringe and the Design of Sacred Experiences”). It is a feeling enhanced by common knowledge—noticing that other audience members are experiencing cringe increases one’s own sensation of cringe, and public preference falsification (as in the case of the Emperor’s New Clothes) may hold cringe at bay. Collins: “The speaker at the seminar increases his or her emotional energy if the audience is responsive… In the opposite direction, the inability to carry off the lecture for that audience… depresses one’s EE. One’s personal level of EE is like a reservoir filled up or drained by the amount of experience on has with such favorable or unfavorable situations…” In other words, we can run out of gas—see Dud stranded on the side of the highway, his lofty narrative hampered by logistics. See Ernie with his ancient car battery, constantly needing a jumpstart.

In the spirit of Eno’s “scenius” concept, Dud is not an isolated “genius” who internally generates heat without input; rather, he is part of interaction ritual chains which charge him up with energy, and his periods of depression coincide with a lack of charge. Either the individuals around him have “deflated” or “popped” the hot-air balloon he uses to get high, or else his expectations of breakthrough have and transcendence have been disappointed. Watch how Blaise enchants (“charges up”) Dud—Blaise has just asked Dud to be his apprentice in alchemy; Dud, honored but anxious, wonder why Blaise has picked him. “Seen and unseen, man. You know what I’m talking about. You got a glimpse of it on the beach, in the [vision of heavenly] light… [in] the star field [you saw] at Orbis.” Dud: “It could just be all the toxic fumes at Orbis, could be all the blood I lost at the beach.” Blaise: “No, don’t do that… [Lynx Lodge founder Harwood Fritz] Merrill had this idea that everyone navigates the world using two maps. The physical map… and the mystical map… Most people navigate using just the physical map, but alchemists move between the two. The daylight world, going to work, eating burritos—but then there’s that other map, waiting down below.” The sacred and the profane; the mundane and the meaningful. The alchemist’s vision—with which he turns the banal holy, the profane sacred—is nothing other than the deeply felt and internalized connectivity of the world. Watch how Dud responds: “I feel like everything in my life is starting to add up. I feel free. I feel free to do whatever I want.” Here we have—temporary and deceptive—the “synthetic dream” so sought-after by Pynchon’s protagonists, a “culminating vision” of a connected and meaningful universe—a vision not discovered through passive searching, but created by Blaise’s active enchantment. The trouble comes when Blaise becomes a fanatic, a maniac, a one-idea man: the alchemical map becomes the only map, the Magnum Opus his only goal. All else is optimized-away, and he “goes into debt,” slowly eroding or undermining all the logistical and interpersonal support systems that allow him to work on the Magnum Opus in the first place, so that finally, bottoming out, he must give up even the Opus.

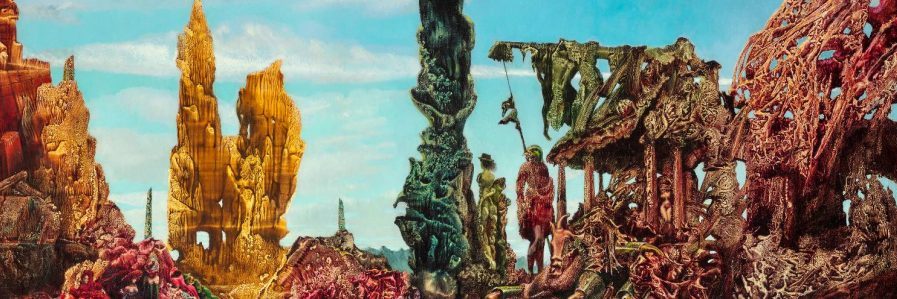

Prospero’s Lysergic Island

He was a wonderful lover, sensitive and quick, with the ability to project a mood that turned the most ordinary surroundings into a scene out of a masterful film—the reeking industrial slum of Manhattan Beach would become as seen through the eye of Antonioni, for example.

Jules Siegel on Pynchon, second-hand report, emphasis added

The morning of the 17th—a little later than planned, perhaps around noon—Caliban and I picked up groceries, headed back to the house, and dropped a tab a piece. As I fed the stray cats of Ponta do Fajã, Ilha das Flores, I could feel it coming up in me, the old lysergic sickness. The cats were trying to get inside, and I started thinking about how a door’s open/shut is an original binary, a primitive and fundamental sort of logic. Blocked or unblocked, stoppage or flow—but of course it’s more complicated than that. The boundary may be semipermeable, may only admit certain kinds of visitors. A cat flap. The hemispheres of Dutch doors. Rolling policies and door codes and the airlock chambers of a foyer.

I listened to the old lysergic melody, in whose rot I smelled a sweetness, as the tooth-chattering and cold-sweats, the muscle tremors and feverishness, that always signal entry into the psychedelic headspace, slowly faded. O’ Iam commander’o’er the seven seas o’ my stomach, n’ having steadied n’ calmed ‘em, can master anything… I sat on the balcony and watched journeyers watch the camino towards the trailhead at the end of our street, coming and going, setting off and arriving, and I felt myself in the sedentary position of the local, although just yesterday I’d been a mobile traveler myself, walking these same paths. And I thought of those way-stations that had helped me along my journey, those locals who knew the path, or provided food and water when I had none—who were sites of information and steadying vibes and a thermos of green tea—and I wanted to be this person for others.

Caliban had taken up a staff of bamboo, and taken to calling himself a wizard, and was looking to wander in the direction of the nearby falls. I made a traveling home base of my bag, with water and fruit and notebooks, a deck of cards and sunscreen for the blazing directness of a mid-Atlantic sun. We were talking magic on the trail; all of our conversations the past two weeks seemed to converge, a dense meaning-mesh17 of metaphor attending every moment. Systems of analogy arose and set themselves on the here-and-now, slipping seamlessly into another system. Meta-rationality, I think—metaphors you rationalize within. Logic and math a set of metaphors made exceptionally coherent. Caliban and I decide that the magical, feedback view of consciousness, and the depth psychological view, are actually compatible. We resolve to avoid the generalizing tendencies of the Western eye, to practice only local noticing.

If magic was vibecraft, then “cool”—as a deflective forcefield we conjure around ourselves, preventing disclosures of interiority—was an entry-level, inter-subjective magic. Impressive when pulled off well—the hazy atmosphere of cigarette smoke; smart-aleck tongue; facial illegibility; after-hours coronet wailing mournfully in the background… But there was another kind of cool—cool as a state of being, not just the front of calm but a real stoic at-peacefulness—which was the epitome of intra-subjective magic. “Ice-veined athletes know: it’s not ‘quit being anxious’ but ‘find a framing you can calmly occupy.’” We’re chattering when up comes a whitewashed plaster home, terracotta shingles, ecstatic synths blasting from the garage, incense burning in the windows. Caliban’s been carrying his phone on his hip, its playlist enchanting the trip, but now the Android’s tinny speakers have been drowned out: “We’re approaching the hut of a powerful local sorcerer.” I record a short video clip on my phone; “one must map powerful magic when one encounters it.” A vibe communicates the implicit terms of engagement; the sorcerer operates in a given geographic realm over which his magic works, over which he sets the tone of interaction. You size up a place’s vibe, it tells you how to vibe with it, how to handle yourself, what sorts of bids will be accepted or denied, what sort of experiences and interactions are possible—and all this space of possibility subconscious, as if charmed. When a spell is properly cast and fully encountered, it’s as if it weren’t even there—it’s just the universe’s timbre of reality. Tolkien, “On Faerie Stories”:

If you are present at Faërian drama, you yourself are, or think that you are, bodily inside its Secondary World. The experience may be very similar to Dreaming and has (it would seem) sometimes (by Men) been confounded with it. But in Faërian drama you are in a dream some other mind is weaving, and the knowledge of that alarming fact may slip from your grasp… Enchantment produces a Secondary World into which both designer and spectator can enter, to the satisfaction of their senses while they are inside; but in its purity it is artistic in desire and purpose…18

Tolkien

Mortar and magic bind the walls of this town together. Force and communication, appearance and reality, physics and pure belief. Faith and Vitamin C bind my ligaments together; they cling in part because they keep clinging. There is no fact about a feedback loop. Mike Oldfield’s “Harvest Ridge, Part One” is playing, bookended by Moondog’s “Pastoral II” and Glass & Shankar’s “Offering.” I think about how I want to spend my life writing spells for people, little charms and words of incantation they can take with them. I think about how I want to fall under others’ spells, want to enchant others’ worlds but also see my own enchanted.

Portals, Postmodernism & the True World

And everything is a portal; people are portals; mistakes are portals of discovery; even sex “is just a door we go through to get to the future.” A portal is a call to adventure, an invitation to questing—to searching for novelty, undertaking journeys together with others, and for changing in the process. “What’s the difference between a portal, a threshold, a doorway, and a gate?” Caliban asks, on the long walk back from town. We’ve just disembarked from an inter-island ferry named Ariel. “What’s inside?” Dud asks Ernie in the series’ pilot, standing at the entrance of the Lodge. Dud’s not yet initiated, he’s just trying to get his foot in the door, to keep the interaction open, as Ernie continually attempts to close it off and shut it down. Later, when Liz asks her brother why he’s so invested in joining the Lynx, he says he hopes it’ll “open doors” for him—business connections maybe, but also “secret handshakes ‘n stuff?”

You follow feelings as a “second map,” not the phenomenal world but the meaningful world. And the philosophy of this show is that delusion and meaning are blurry phenomena. Delusions make themselves true, or carry metaphorical truth, or are necessary means for bringing communities together. The show’s full of emperors with no clothes, sovereign protectors living on borrowed time: living on credit, trying to keep up the act long enough for a final disappearance before things come crashing. Bullshit artists that keep the magic alive for everyone.

“I’m done looking for a door to another world,” Blaise swears off. Dud, resigned, is tempted to agree with him. “Cuz that world doesn’t exist.” But Scott’s grown up by coming to a different conclusion. “I’m in a new place. We all are. It’s scary.”

The secular framework of modern bureaucracy is a disenchantment machine par none. “My therapists here think my Hollow Earth theory is a coping mechanism, I’m looking to escape this world. Windows, mirrors; maybe one of them is a portal to some place new.” A hollow earth theory promises a hidden truth, beneath appearances, which lies at the center of being; at the same time, this hidden essence turns out to be nothing more than emptiness. “There’s an entire world beneath our feet.” A desperation to get past or beneath surface, to get to the heart of things, the true world, the true lodge. Or see the shot of Scott coming up through the suburban lawn—the ordinary shot of an ordinary lawn, which suddenly, subtly, begins moving, only to reveal an underground, a series of tunnels and bunkers, a network of connections between places and people that is unknown to surface-dwellers. (This suburban lawn motif nodding to Lynch’s Blue Velvet, but also the California water crisis and droughts.)

There is no true world, nor a true lodge. No paradise, no panacea—only more flawed worlds. No final solution, on an endless sequence of improvements and fixes. No “other side,” just an endless series of backrooms. No final guru, only a series of mentors. And yet somehow, this stance refuses to contradict the value of stepping through portals, of seeking and questing. Jacob Clifton, in his brilliant essay on True Blood and Alan Ball, writes:

In Alan Ball’s fictional worlds, [the guide who shows our heroes a new world is] invariably a drug dealer. American Beauty’s Lester Burnham has only taken a few steps off the well-lit path before he meets young pot dealer Ricky Fitts, and falls in love with Ricky’s consequence-free approach to life. Nate Fisher’s accidental ingestion of a tab of E in Six Feet Under leads him to a dreamy poker game underworld where his father introduces him to spirits of Life and Death and he sees their raucous and hilarious lovemaking for himself. And then there’s True Blood, where the drug of choice is vampire blood. Because there is something revolutionary about letting ourselves fall that deeply into our own chaotic worlds—a little bit unruly and a whole lot terrifying—the “illicit drug dealer” metaphor continues to carry weight. It’s a given in Ball’s world that the divisions between and within us are created and enforced by society at large: how better to dramatically enact the wildness, the suspect freedom, of tossing all that shame and appropriate behavior than under cover of darkness? …it represents succumbing, on some level, to temptation. Stepping out into Crazy and seeing what you can find.

[…]

The subversive power—and I would say, a bit of the popularity—of each of Ball’s stories is that the Guides presented are never eternal, never reliable, because nothing is eternal, norreliable. There is no Answer that is always going to be the Answer. In fact, a good rule of thumb for all three narratives is that once something becomes the Answer, it stops being the Answer. Whether it’s Ruth Fisher’s “personal development seminars” or Lester Burnham’s free-flying midlife breakdown, the Answer immediately begins to rot around you the second that you find it. Brenda Chenowith’s sexual awakening becomes too dark to look at; Sookie and Bill’s immediate mutual obsession falls into domestic disagreements about stepdaughters and “us time”; Tara’s discovery of Miss Jeanette’s true identity sends her into a full-on meltdown complete with gaudy prom dress. You cannot simply turn a corner in your life and become a new person. Thinking that you can is how you end up in a cult. Or lonely, or addicted. But if there’s no place to rest, no fixed answer, what’s the point of these stories? Temperance. Balance. Because for each character in these stories, there is a choice to be made between abandon and repression, and it’s a knife edge we all have to walk.

…Ultimately there’s nothing easier than retroactively crossing [a Guide] off your personal list of “good people” and discarding any good they’ve brought [about]… I would argue that to judge or discard the Guides [misses] the point entirely. People aren’t “good” or “bad”; they’re people… The question remains, as in all of Ball’s work: Where does the Guide stop being useful? When should you hop off the train and find your next answer?

Afterword

The second prejudice or tacit assumption [of philosophy] is that the criterion of truth exists in free-floating reality, along with the free-floating thinker-observer. But the very concept of truth has developed within social networks, and has changed with the history of intellectual communities. To say this is not automatically to assert either self-doubting relativism or the non-existence of objectivity. It is no more than a historical fact to say that we have never stepped outside of the human thought community… [and] never will step outside of it. The very notion of stepping outside is something developed historically by particular branches within intellectual networks…

Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies, emphasis added

In the end—well, there is no end. Only with an ending is closure achieved; only at dusk does Minerva’s owl trace the sky. To “wrap up”—to put a tidy bow on things—there is a violence in bracketing. We want a final answer, a final system, transcendence from the labyrinth. Instead there is only enmeshment and interconnection, resisting our attempts at separation. “The persistent irony is that human beings are never allowed to transcend their condition,” writes Molly Hite in her book-length critical study of Gravity’s Rainbow. “The impulse to provide conceptual unity traps consciousness in its own labyrinth.”19 The quest for logical coherence necessarily entails a disregard for the richness of local complexity, in favor of some annihilating, hygienic system of abstraction.20 “To objectify experience as a conceptual unity is to ‘go over’ to the side of the anti-human and the gods, to side against life.”

Writing this text, I keep trying to square details away, ensure the symbols are consistent, keep everything tidy. One system to rule them all, at least for a while, at least for now. But by now I know that’s not gonna happen, and that’s likely for the best. I’ve built my own labyrinth; trying to solve it in the pursuit of a punchy concluding line is more Pynchonesque futility. “As Slothrop’s heretical ancestor William suggested, the things that do not fit may be the most important because they bear witness to the inability of the providential schema to account for everything…”21

All these incoherences, all these vying analogic scaffolds. But perhaps we ought to slip smoothly between similes, and baloney to he that reifies a temporary taboo on mixing metaphor. This is how the mind “naturally” thinks on psychedelics—the everything-connectedness of the associative web. Have you noticed that the further you strain to extend a metaphor, the less sturdy and substantive the connections seem? It’s tautological; only some aspects of two disparate objects can ever coincide. In one way, our topic’s like a water wheel; in another, like a clock, and bow’n’arrow; in another, it’s like the sun as it travels across the sky.

The problem with Liz and Dud is they live in the partial-logic of one set of metaphors; they are Chestertonian maniacs caught in the prison of a single idea, the same way Oedipa’s trapped in her binary constructions, insistent that the world’s either sacred or profane, that she’s either at the center of an elaborate plot or just hallucinating. The logic of power is so simple, and so banal, and yet so different from the propaganda. See, imaginatively, the parallel structure of W.A.S.T.E.’s muted postal horn, and the XOR gate of circuit-logic:

Pynchon and Jim Gavin, Lodge 49 showrunner, both endorse the projecting of worlds—enchantment, meaning quests, world-construction. But they reject treating any world or system as “the” system. Additive, not substitutive. To see stereoscopically, viewing “two different pictures at once and yet” seeing “all the better for that” (Chesterton, Orthodoxy). This is the sort of Magic Eye or “auto-stereographic” vision sometimes ascribed to Pynchon’s books: “patterns printed in two dimensions on a flat page that, when the eyes diverge, become startlingly three dimensional.” Only by viewing two separate patterns simultaneously, so that they are layered on top of one another, does the subject “come to life.”22

Experience that stacks, rather than constantly overwriting itself. Balancing meanings, pursuing goals that are complementary and Pareto-affective across frames, rather than go all in on a single map, a single conceptualization, a single telos. Rather than making all-in bets, just to prove to themselves they hold a winning hand. To prove to themselves they’re on the heels of the True Lodge, that they navigate with the True Map. Meanwhile the compound interest racks up, all the bad trade deals catching up to them. If their gamble fails to pay out, they have nothing. If their gamble succeeds, they simply delay the inevitable. Russian roulette is a non-ergodic game; eventually, no matter how lucky you are, you’ll blow your brains out. There is no winning long-term, with a losing strategy. When Juana, in Steinbeck’s The Pearl, says that it is not good to want a thing too much, or the gods will punish you, we can translate her wisdom into our secular stock of truisms. That “haste makes waste”; that in “venturing all our eggs to one basket,” we risk total disaster; that an unbalanced single-mindedness is a self-destructive force.23 From the East, we might compare wu-wei’s trying not to try; in the study of tradeoffs, we can understand the impoverishing effects of single-mindedness through diminishing-return curves.

What have I accomplished here, except endlessly stacking metaphors? I hoped to simplify and clarify, to cut down and compress the original materials, but all I’ve accomplished is a series of annotations. Not less text, more text. Endlessly accumulating information where I’d hoped for reduction.

There are many true ways a story may be told, for all stories are at best partial representations, which allow other partial representations to challenge their authority. To privilege a story, and the partial reality it represents, on the basis of its “truth” or rationality—with no eye towards pragmatic outcome—is to fail in our duties to our fellow men. To seek an ultimate conclusive schema, necessarily involving an exclusion of “recalcitrant elements that refuse to conform,” is to align oneself with Pynchon’s Calvinist God, who in choosing an elect for salvation, “damns the preterite aspects of his creation.” Noah Cross: like the Biblical Noah, picking who lives and who dies. The pruning of a careful gardener… Setting the terms of the future, by the picking and choosing of persistent parts…

Thanks to Gianni de Falco, Galen Cuth, Ari Holtzman, the Wizard Caliban, and Nicole Kaack for giving this project energy and material.

End Notes

- Ernie, in the fall-out of several strung-along disappointments: (1) Connie’s reneged promises; (2) Larry’s fraud and Avery’s fraud, disappointing Ernie’s hopes of Sovereignty and a Grand Tour disappointed; (3) Captain’s fraud, disappointing Ernie’s hopes of the Orbis deal. Ernie just gets hammered, repeatedly; it’s hard to call his disenchantment anything other than a return to the real. ↩︎

- This is partly why the Orbis corporate ladder loves Liz: she’s somehow immune to others’ bullshit (if not her own); she’s able to see through their enchantments (“You have a non-traditional resume”) and peel back the surface-glam to what people are “really” saying (“You mean shitty; I have a shitty resume”). But then she’s also, selectively, able to “turn it on,” go from disenchanting to re-enchanting, at least in corporate workshops when her back’s against the wall. An early corporate training exercise sees her leading a group project, needing to spin a compelling brand narrative from three assigned objects—a whip, a grail, and a crystal ball. Structurally, this is an almost exact parallel to Dud, a fellow initiate who catalyzes his social sphere to “constellate” and “contextualize” the Lodge’s materials in narrative. (In other words, alchemy.) ↩︎

- See e.g. her responses to Eugene’s courtship and Janet’s mentorship offers. ↩︎

- “There is certain magic to romance, according to the common lore of love, a spell, that infatuates, that transforms mundane, expectable reality into something transcendent, a kind of personal domain of the sacred. Romance is an altered state of consciousness… it turns the monochromatic into Technicolor,” psychologist Stephen A. Mitchell writes in Can Love Last?. Ernie uses music metaphors to say the same thing: “In my experience, it comes on like an orchestra warming up. And then—the music is just playing.” ↩︎

- The philosopher’s stone, the magnum opus, the holy grail, immortality, paradise, the pearl of the world—all the same thing, all the same thing, all the same search for transcendence, for the highest of holies. ↩︎

- “L. Marvin Metz” is almost certainly a reference to the (equally graphomanic and braggadocious) L. Ron Hubbard, who claimed extensive invented credentials as an adventurer, and managed to charm the rocket scientist Jack Parsons out of both fortune and lover. ↩︎

- Something explicitly referenced in Lodge 49‘s “Parabola Group,” a dark-money military-industrial offshoot of Orbis that tries to convert alchemical knowledge into weapons research. ↩︎

- Charles Laughton reading Phaedrus, sourced in Malick’s Knight of Cups: “Once the soul was perfect and had wings… It could soar into heaven where only creatures with wings can be… But the soul lost its wings and fell to Earth… There it took an earthly body. And now, while it lives in this body, no outward sign of wings can be seen. Yet the roots of its wings are still there. And the nature of wings is to try to raise the earthbound body and soar with it into heaven.” ↩︎

- The cost Oedipa incurs, in Lot 49, metabolizing chaos into order is a central theme of the novel. At one point, she meets a man who claims to have invented a motor built atop a real-life Maxwell’s Demon. The sorting work that such a demon would have to perform, however, always outstrips the energy it produces through sorting. ↩︎

- This tower metaphor—which is namechecked explicitly by Captain in a S1E8 self-description—is one of the structuring metaphors of Lot 49; Oedipa is described as trapped Rapunzel-like in a tower of her own mind, the limits of her closed world. She is both terrified of what lies outside this tower—early in the book we see her literally self-insulating, and twice refusing the call to adventure—and highly desirous of escape. ↩︎

- Weber: “Without prior consultation with the magician, no innovations in communal relations could be adopted in primitive times. To this day, in certain parts of Australia, it is the dream revelations of magicians that are set before the councils of clan heads for adoption, and it is a mark of secularization that this practice is receding.” ↩︎

- Everything the prophet touches becomes possessed of this aura—the cloth that wiped sweat from his brow, the thorns that pierced his forehead, the leather of a sandal-strap:

One Sunday this May, hundreds more hopefuls stood in a line that began at 6:00 a.m. and ended by wrapping around a Broadway block twice. These boys and girls were there to buy “it.” They were there for an event advertised as the “Sale of the Century.” They were there because the things being sold belonged to actress Chloë Sevigny…

Magical items, relics, enchanted by their contact with a holy man, saint, prophet. They are trying to purchase and own a bit of “aura,” Kan-Sperling tells us in “Second-Hand Lifestyles.” The second-hand lifestyle is Pynchon’s metaphor too, for the (ultimately fraudulent) images of identity that consumer objects (and their tube-advertising salesmen) promise. Mucho Maas, husband of Oedipa and ex-used care salesman, has a crisis of faith in his dealer-gig which centers around his realization that the business sells “futureless, automotive projection[s] of someone else’s life” to clients—fuselages carefully calibrated to communicate a certain type of guy, a certain lifestyle, a certain class identity—but inside full of “sick transmissions” hushed with sawdust, rusted-out undersides and malfunctioning engines. ↩︎ - Robert Stalnaker, Context & Content, writes: “The essential effect of an assertion is to change the presuppositions of the participants in the conversation by adding the content of what is asserted to what is presupposed. This effect is avoided only if the assertion is rejected.” Implicit here is the idea that part of the common ground or context, in interaction, is not explicitly viewed as an assertion which is accepted or rejected as such by receivers. ↩︎

- “Don’t worry about your foot Dud, I’m gonna fix it. I had a crisis of faith but now I feel like anything’s possible.” ↩︎

- Ioan Petru Culianu ↩︎

- Lodge 49 references The Tempest repeatedly; see e.g. the first season’s finale, “Full Fathom Five.” ↩︎

- Maas (as in Mucho & Oedipa) is a Dutch word, signifying a W. European river as well as the concept of mesh, the open spaces between a net’s threadwork, or a legal loophole. ↩︎

- Tolkien distinguishes this enchanting art of weaving Secondary Worlds—of “sub-creation”—from wizardry and magic, which he reserves for attempts to “produce an alteration in the Primary world,” often for the purpose of power. It’s an intriguing distinction but one too nuanced for this text, which in connecting dots, foregoes distinctions between wizards and prophets, scammers and confidence men, enchantment and rhetoric, delusion and illusion. ↩︎

- This is precisely how Oedipa is trapped, having encountered a “secret richness” and “concealed density” beneath the Californian surfaces, and then reducing the possibility interpretations to a neat 2×2 grid, a “symmetrical four.” ↩︎

- cf. James C. Scott’s work on legibilization, rationality, and imperialism in Seeing Like A State. ↩︎

- Hite, ctd. ↩︎

- Charles Hollander, “Pynchon, JFK, and the CIA: Magic Eye Views of The Crying of Lot 49” (1997). ↩︎

- The Lodge’s Sovereign Protector, Larry—as if gifted fire by Promethean scroll-stealers—once had everything, was in possession of Merrill’s sacred scrolls, and he threw it all away, bet it all on one game of poker, on one hand, just kept doubling down until he had nothing except the scrolls left and then lost those too. He spends the end of his life questing to replace that loss—and in vain. ↩︎

Leave a comment