This is a lightly edited version of a talk given at Fluidity Forum in September 2023. Expect scattered transcription errors.

A few years ago, some friends and I started a group called The Inexact Sciences, or TIS for short. We run a group blog called tis.so that some people might know. And we took as our mascot the pfeilstorch, or “arrow stork.”

Until the 19th century, nobody knew where birds went in winter. It’s one of those things that seems so straightforward, but in fact they had all kinds of wild theories, like maybe they’re going to the moon, maybe they’re transforming into different kinds of animals, and then in spring they transform back to birds. Maybe they’re going underwater and hibernating there.

And then sometime in the 19th century, somebody in Germany was going out to hunt storks that were flying overhead, and shot one down, and it had an African spear in its neck. And this happened a couple more times before they realized, oh, all these birds have been to Africa and back. And it’s one of these really freakily rare occurrences where somehow this bird got speared by somebody a continent away, survived, flew to another continent, and then was shot down.

But if you just find a couple of these guys, you basically know how bird migration works. And so we usually have this idea that the only way science can work is with very large amounts of data that you collect and perform math on. And in fact, the role of the anecdote here is clear, where if you have the right kind of anecdote that’s load-bearing in the right ways, you can do a lot with it.

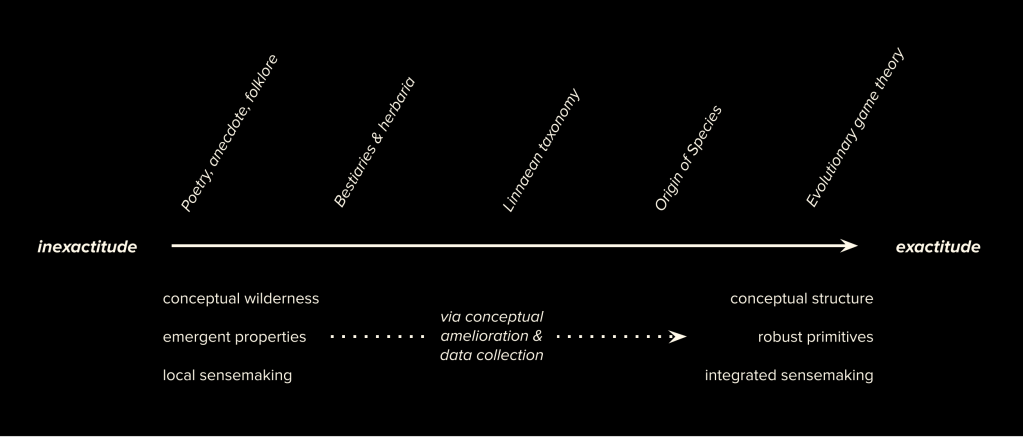

One of the early conceptual metaphors that we started working with was the rigorizing pipeline. It’s a way of conceptualizing how subject domains, or areas of inquiry, move from inexactitude to exactitude, move from being this fuzzy nebulous thing that we can only talk about very informally or through art, and ends up where we have a logically tight evolutionary game theory being run through mathematical models.

And not to get into the full process, but for instance with biology, we start out even just four or five hundred years ago where you have all these local ~species concepts, so that you can travel to two English villages that are 20 miles apart, and they’ll carve up “black birds”—birds that have varying amounts or shades of black-ish feathers—totally differently. And natural philosophers would go around, just surveying the names used in different regions, the different lumpings and splittings, and compile them into massive bestiaries and herbaria. Pretty soon you have Linnaean taxonomy. Once you have Linnaean taxonomy, you can get Origin of Species, but I don’t think you can have a Darwin without some basic descriptive sense of the territory.

Eventually we can model the game theory of evolution, but it’s the result of a long conceptual amelioration process, where the concepts are being continually redefined to be more and more stable, so that they eventually end up somewhere mathematically robust. Somewhere you can apply the level of pressure you might be tempted to apply. And our thought was that a lot of fields get tempted by the prestige of capital-S Science and they end up jumping ahead, and skipping the important descriptive work for something statistical. You see a similar thought from Literal Banana in “Against Automaticity,” that we need fewer lab studies and more phenomenology.

So this is where the Lewis & Clark Linguistics idea comes from, and the role it’s trying to serve. Our “Lewis” in question is David Lewis, an American 20th century philosopher who studied under Quine and Iris Murdoch, and mentored Brandom. And the “Clark” is Herb Clark, a psycholinguist out of Stanford and author of Using Language. I’m not going to define Lewis & Clark Linguistics yet, but I think in many ways it’s a commonsense account of language. It might not surprise anyone here. But I also think that, if we took it seriously, and used it to refactor our communications theory stack, it would contradict a lot of the ways and heuristics we use to think about how language works.

I’m just going to throw out a bunch of sentences that I think don’t sit very well with the view of linguistics that I’m about to enumerate. You can see how many you agree with, and then maybe at the end you can reflect on how Lewis & Clark as a “fundamental” or foundational layer matches or doesn’t match up with these.

- What matters is telling the truth separate from the consequences.

- I didn’t “mean” anything, I’m just stating a fact.

- I prize authentic self-expression as the highest form of communication.

- I dress only for myself.

- I’m not trying to “do” anything or change anyone.

- I have no agenda when I hang out with my friends.

- It’s almost always unethical to manipulate others’ behavior.

- Strategizing about social interaction leads to clunky, forced, artificial feeling interaction, and you’re best off refraining.

From Manipulation to Coordination

Back in college I wanted to be a writer and, because I was hanging out in humanities departments and wanted to learn about language and how words worked, I got into literary theory, read a lot of continental, from Saussure to Derrida, and then moved into the analytic tradition. And to be honest, I found both frustrating in terms of how they talked about language.

I found that people often talked about communication in terms of information transfer, as if you were passing physical objects back and forth, or language as this structure, this building that had been built and stayed in the same place and constricted all its inhabitants’ movements. And I was trying to move beyond these metaphors and framings because I found them misleading.

My hunch was that communication was best modeled as a form of manipulation, a sort of indirect force. And in researching this idea, I came across a great 1978 paper by Dawkins and Krebs called “Mind Reading and Manipulation“, and its basic thesis is that the signal is a means by which one animal makes use of another animal’s muscle power, which is what Dawkins called manipulation. A really straightforward example of attraction and repulsion, a male cricket chirps so that female crickets move nearer to him. Or more radically, a canary song causes a female canary’s ovaries to open, something that the female canary can’t do on its own.

So then for a while, I was pushing this idea that All communication is manipulation. Wrote a series of essays, and I’ll blow through this quickly, but very specifically what I meant is all communication is behavioral manipulation. There’s a way in which putting images in people’s heads, or making people imagine things, is a form of action. But it’s not a form of action that you as a speaker can ever audit or experience. You’re not privy to it, and so you can’t possibly optimize for it. The best you can possibly hope is that you’re optimizing for people’s self-reports. This is similar to the classic Wittgenstein beetle-in-a-box, when he talks about pain.

And then just to be totally explicit about what I mean by manipulation, the function of language is to alter other agents’ actions. Full stop. There’s a reading of J.L. Austin’s How to Do Things with Words where Austin makes a very similar argument, starting his lectures by saying, “Maybe there’s this special category of language called a speech act that behaves a little differently.” A speech act being something like saying “I do” in a marriage ceremony, or naming your child or your sailboat, where an individual creates reality with language, as much as describing it. And what happens over the course of his How to Do Things with Words lectures is that he slowly complicates this picture to the point where it’s unclear whether any speech isn’t a speech act. This is, I think, another way of saying all communication is manipulation.

And I’ll give an example, to make this more intuitive, because I met a lot of resistance when I started describing communication as manipulation. Manipulation is a “bad word.” I wouldn’t recommend advocating for this thesis to friends unless you want to have a hermeneutics of suspicion applied to your every utterance. This mistake was really a failure to internalize my own thesis, because if all communication is manipulation, what was I trying to do, going around telling people?

But once I described concretely what I meant by manipulation, a lot of resistance went away. Perhaps my fault for choosing the word “manipulation,” but I’m not sure there’s a better word. And I’ll just read you really quickly an illustrative passage about my childhood.

When I was young, my mother would wake me up each morning for school, opening the door and saying my name. When I got older, the alarm replaced her. Snoozed by button press or verbal assurance, their follow-ups would nag me out of bed, ensure I was up and dressed. Perhaps my mother would ask me what I wanted for breakfast, and then I would tell her, and then she would either make it for me, or supply the materials from high shelves, so I could make it myself. I would read the cereal box ingredient lists and nutritional charts as I ate, text written to influence purchasing decisions I did not make. Or the stories and puzzles on the back designed to entertain children in “educational” ways, which is to say, marketing for my mother with potential positive knock-on effects for the kiddies. She might remind me to pack certain articles of homework, to not forget binders or pencil packs, might tell me the weather to guide my dressing or insist I wear a specific item of clothing.

“A Landscape of Communication”

We live in this incredibly rich environment of signals that we’re constantly putting pressure on and referring to. This gets back to Collin Lysford‘s talk this morning, about how much information the environment stores, about how we offload computation onto the environment. G.K. Chesterton once wrote that the 19th century detective novel was the first art form to really capture the jungle-like semiotic density of a city, so I’ll quote him briefly:

The first essential value of the detective story lies in this, that it is the earliest and only form of popular literature in which is expressed some sense of the poetry of modern life… The lights of the city begin to glow like innumerable goblin eyes, since they are the guardians of some secret, however crude, which the writer knows and the reader does not. Every twist of the road is like a finger pointing to it; every fantastic skyline of chimney-pots seems wildly and derisively signalling the meaning of the mystery.

…there is no stone in the street and no brick in the wall that is not actually a deliberate symbol—a message from some man, as much as if it were a telegram or a postcard. The narrowest street possesses, in every crook and twist of its intention, the soul of the man who built it, perhaps long in his grave. Every brick has as human a hieroglyph as if it were a graven brick of Babylon; every late on the roof is as educational a document as if it were a slate covered with addition and subtraction sums.

Back to Lewis & Clark Linguistics (LCL). So, after meeting a lot of resistance to “all communication is manipulation,” and guided in part by the hunch of A. Holtzman, who will present later tonight, I tried an alternate tack, which in many ways is a reframing or rephrasing of “all communication is manipulation,” but which brings out and makes salient different aspects.

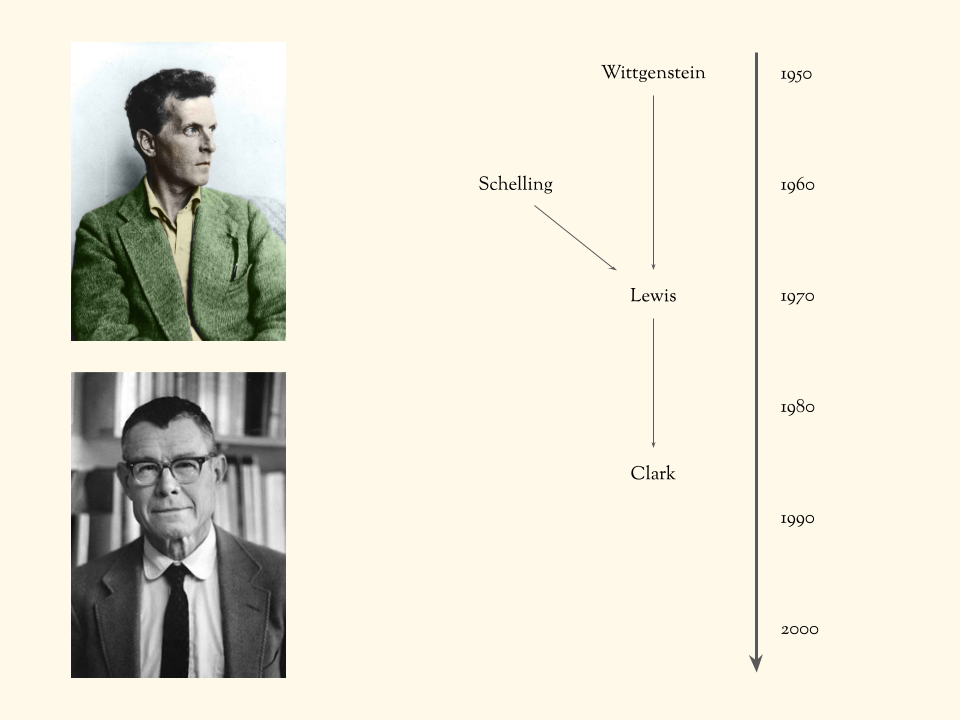

But first, where does LCL come from in terms of lineage, because I think what’s important here is understanding that this is a minority school in philosophy of language, and although many incredibly influential philosophers have been part of it, somehow their takes haven’t been fully integrated or wrestled with. David Lewis’s main influences, in his thinking on linguistic convention, are Thomas Schelling’s Strategy of Conflict and Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. Lewis publishes Convention in 1969, which is within fifteen years of both of those texts publications. Clark shows up a decade or two later. But I think that the L&C theory of communication is already implicit in Shelling. It’s almost like the dark matter of Strategy of Conflict. That text is all about how people tacitly coordinate—how people coordinate without using language. And he says, you know, it’s surprising, we’re actually not terrible at this, sometimes we can in fact coordinate without communicating. And obviously the unsaid thing here is that usually the way we coordinate is using language. Wittgenstein makes the same case in his classic builder’s example in PI, where a team of builders are trying to construct something, and they have a simple toy language to get that done together.

So to recap, we play language games to get things done; words are sort of like a tool, and Schelling introduces the game-theoretic coordination problem framework. Schelling, in a kind of radical break from earlier game theorists, made the really important observation that in the real world, in any situation, agents are going to be both aligned and misaligned. Neumann and Morgenstern’s Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944) had focused on zero-sum games like chess, but there’s no such thing as total alignment. There’s no such thing as total misalignment either, and this is why there’s also no such thing as total war. There’s always some amount of common ground. You see this in the Cuban Missile Crisis. And in terms of misalignment, even people who are ostensibly cooperating in a company, they’re going to run into surrogation problems where you have to rig up really complicated incentive structures in order to secure alignment.

The classic example of tacit coordination is, Schelling surveys a bunch of people, and he says, you have to meet up with somebody in New York City tomorrow. You can’t talk to them. No communication. Where are you going to go, and when? Respondents have to pick both a time and location, and 80ish% of people say “The information booth, at Grand Central, at noon.” This is incredible. It’s cherry-picked, but the fact that someone who’s never even been to New York could pull this off is amazing.

The thing about language is that we can meet other places other than the information booth at Grand Central at noon. We can spin up really novel, intricate, flexible coordinations, and we’re also able to continually renegotiate those contracts. If people are familiar with meeting up with somebody somewhere before cell phones, versus after, being able to communicate via text means that you can continually renegotiate. “Oh, do you actually want to meet next door in the coffee shop?” You can’t do that before because you don’t have communication. You either cooperate and follow the contract you agreed upon, or you defect and don’t show.

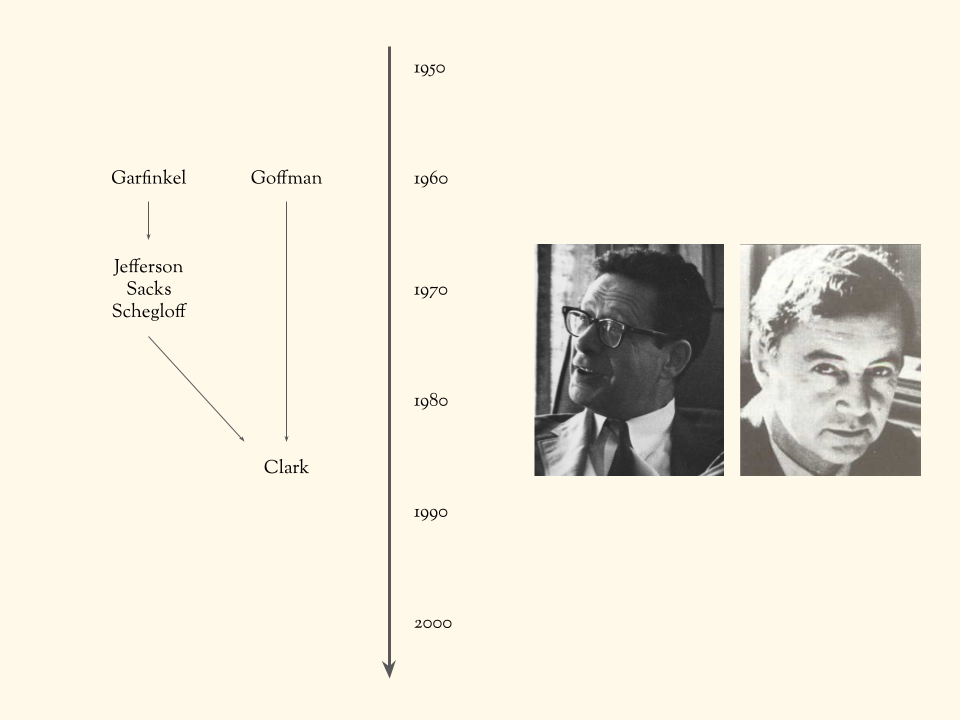

There’s also an alternate school that I think runs parallel to this philosophy of language trajectory, and it happens in ethnomethodology and microsociology. Audience members who read David Chapman might be more familiar with the ethno side—Garfunkel, Jefferson, Sachs. This school ends up influencing Herb Clark; he cites Goffman and the ethnomethodologists frequently in Using Language, which is partly why it’s relevant. But their ideas were that if we want to understand the “meanings” of people’s actions, we have to understand outcomes and how an action alters other agents’ outcomes. It’s an action-oriented approach, that skirts around mental representations and steps into the knowable world and how expression cashes out. Which is a very American pragmatist way of thinking, perhaps bridged by George Herbert Mead, a founder of American sociology who was strongly affiliated with philosophical pragmatism in the early 20th C.

Goffman was really, I think, first and foremost a communication scholar, though he’s rarely talked about that way. His most influential book is Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. It’s concerned with how, by presenting one’s identity in different ways, one acts to control and manage situations. The second text relevant here is Strategic Interaction—less read, but crucially for our purposes, it builds on Schelling’s ideas. It’s about espionage and warfare and coordination problems.

One of the other important things Goffman pushes is bringing an ecological framework into sociology. To him, living organisms are always “ecologically huddled.” They’re always proximate and observing each other, and they’re interdependent in their outcomes. They’re always reading and writing to their environments, to other organisms. This is one of those things that in TIS we’ve referred to as generalized reading. This is the idea that if an agent (Agent 1) is emitting information, or behaving in some observable way, that correlates with outcomes that some observing agent (Agent 2) cares about, then Agent 2 will start changing their actions based on their observations of the Agent 1. And if Agent 2‘s changed actions correlate with outcomes Agent 1 cares about, Agent 1 will start managing and manipulating their own emission of information in order to manage those outcomes. Agent 1 has become a full-fledged writer. This is the shift from a “cue” to a “signal” in ethology. And now suddenly Agent 2 is watching their own emissions and actions, to manage and manipulate Agent 1. They’re both involved in this recursive mutual modeling and managing.

Features of the Game

Now, in the 60s, the “games” metaphor is a big deal. Everybody uses games as an analogy for social interaction, and somehow it disappears or goes out of fashion. I haven’t totally figured out why or when. It would be worth tracking the sociology of this. The metasociology.

There’s Wittgenstein’s “language games” in the late 50s, of course. But you also have Leonard Cohen’s Favourite Game, Lyotard’s Just Gaming, Eric Berne’s Games People Play. It’s all over music and pop culture—Joni’s “Circle Game,” Dylan’s “only a pawn in their game,” Lennon’s “Mind Games,” Jackson C. Frank’s “Blues Still Run the Game.”

And I like the “game” metaphor, because even if it’s out of date and people think it’s crude, it’s basically the native arena for action, right? It’s a sort of simplified small world, to use Anna Riedl’s language earlier this afternoon. A magic circle has been drawn around action. I think this small world thing isn’t a coincidence, because I think there’s a close link between our notion of games and the small world’s notion of a frame. The frames people possess both create the game, and are created by the game.

So getting back to Lewis & Clark. We’ve outlined this larger action-oriented context in sociology and linguistics, that’s functional and pragmatic. The form of language serves the social problems that language solves. Language is as language does; it’s a cultural practice, not an object; it’s a social technology; it can only act through its effects on agents. I can’t move a rock or build a wall with language on its own. I need to use an agent as an intermediary.

In a lot of ways this is clearly compatible with the communication as manipulation frame, but here we stop thinking about action from the perspective of a single agent, and we start thinking about joint action from the perspective of a social body. Joint action is ecological; when we jointly act, outcomes are interdependent. We’re all engaged in prolonged joint action here at this conference, and really whenever we’re around other people. There are plenty things I can do that will mess up your day, and vice versa.

So communication is used to negotiate and coordinate action. And language itself is a form of joint action undertaken to solve coordination problems. Because it’s a form of joint action, it poses a further series of coordination problems. So you have this two-step where we’re solving coordination problems in order to solve other coordination problems. Language as means to non-linguistic ends. And we should therefore expect that the form of the problem of linguistic coordination, and of the solutions to linguistic coordination problems, are very similar to those of coordination generally.

And crucially, language, I think, only emerges when there’s sufficient interagent alignment. You can think about poker as a sort of foil: ideally rational poker players would never speak or emote, because none of the other ideally rational players are updating based on their expressions, so their expressions are pointless. And so all agents, following Shelling, are somewhat aligned, but there has to be some sufficient threshold of alignment. Or perhaps more accurately, communication between agents will only emerge to produce outcomes in situations where the communicating agents are sufficiently aligned in their goals.

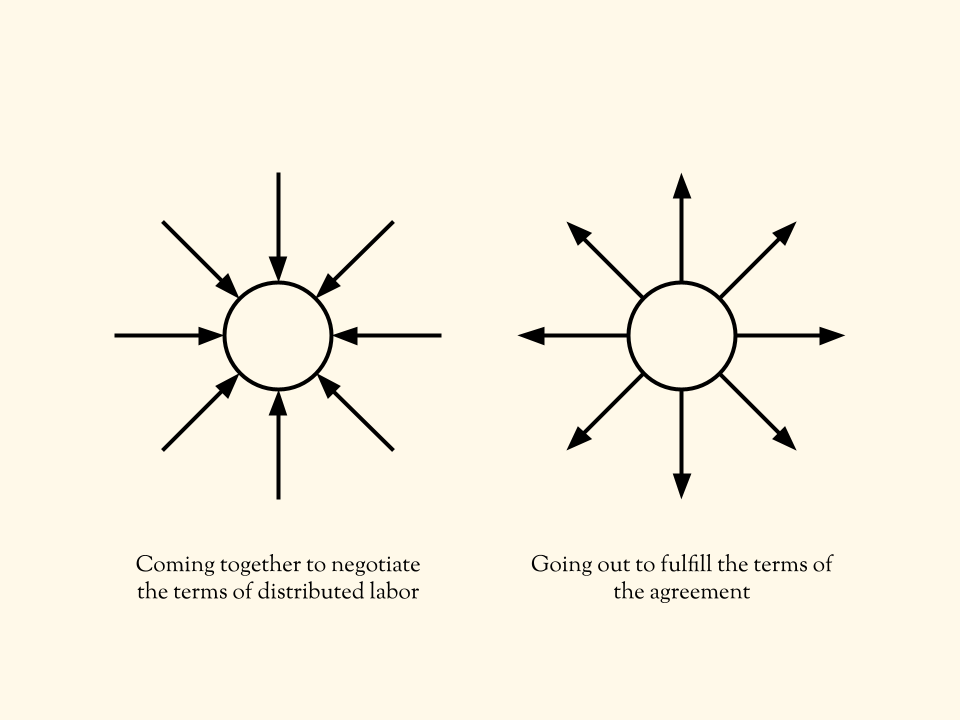

One of the really common patterns we see in communication and coordination is that people come together to discuss the terms of their distributed labor, and then they go out into the world and they perform distributed labor. So this could be a boardroom or conference table, a parent-teacher meeting, a timeout huddle in a sports game.

Another important pattern is the use of some fixed pattern to coordinate around. This helps solve some of the recursive mutual modeling problems. Let’s take dancing. You can’t dance in sync without communication. Without language, yes, but not without communication. To stay in sync with others, there typically needs to both be some advanced agreement or “contract,” and also a constant feedback loop of monitoring and signaling, reading and writing to one another. This is very typical of coordination: it gets worked out in advance, and then we ambiently monitor whether others follow through and carry out the contract’s terms. Now, dancers’ staying in sync can be stigmergic, and we’re going to talk about what stigmergy is soon.

Now, those who attended Feast of Assumption’s waltz lesson this morning know what I’m about to say, which is that, in waltzing, it doesn’t matter which foot you step with first, so long as it’s complementary to your partner’s choice. Otherwise you end up stepping on one another’s toes. There’s a reason this phrase is so universal, because it tells us something important about communication. This is the rigorizing pipeline.

The other key thing about dancing is it would be very difficult without a beat. You’d do all this recursive modeling. A beat saves you from this, because you can just trust that each dancer is going to synchronize to the beat, and synchronize yourself to the beat in turn, and now you’re all synchronized to each other. This is something Morgan Butkiewicz turned me onto, which comes up in Karl Friston’s paper “Duet for One.”

And I think talking about how information is offloaded into the environment very much apropos of Collin’s talk. I think one definition of cooperation would be that you are maintaining load-bearing regularities in the world. You are stabilizing the patterns in the world that other agents depend on because all their strategies, all their knowledge, all their information are just pointers or heuristics that assume a certain environmental state. As long as the environmental state stays stable, they remain efficacious in achieving their goals. Now on the other hand, when you defect or when you are in conflict-dominant situations, what you do is you actively change the distribution. You try and move people to distributions where they’re less efficacious. You try and move the environment to places their heuristics aren’t set up to be efficacious in.1

And I guess lastly the thing I’ll say when we’re talking about beats and technologies which allow us to sync up and entrain, I think we have this repository of resources that allow us to coordinate. I think that’s basically what culture is. I think that collection is culture. Okay, moving forward.

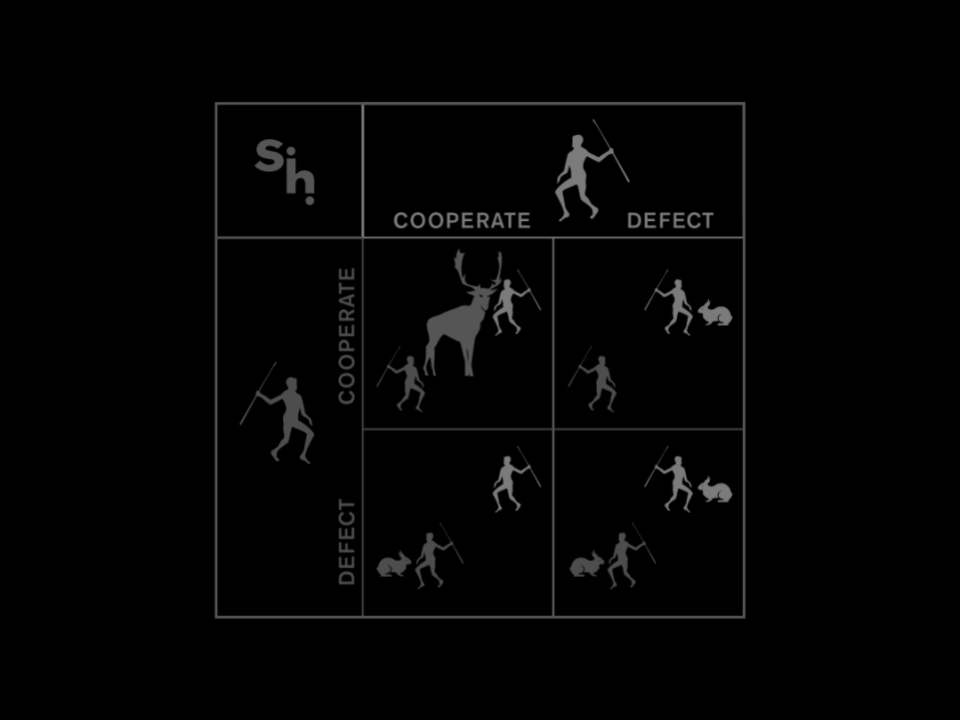

Classic example from game theory, you have the stag hunt. And for those who don’t know what the stag hunt is, here it is broken down:

The basic premise is that you and your neighbor are going to go hunt in the woods behind your houses every day. Each of you can either bring stag hunting equipment and hunt stags together, and you’re, let’s say, guaranteed a stag. Or each of you individually can bring rabbit hunting equipment. You can hunt rabbits alone. But you must hunt stags together to catch one. The premise here, very similar to a prisoner’s dilemma, is that maybe you’ll get less meat if you individually catch rabbits, but it’s sort of okay if you both defect. If you both coordinate, you secure the greatest caloric return. And the worst case scenario, if there’s a mismatch where one party is cooperating and brings stag-hunting equipment, and the other defects and brings rabbit snares, someone is going home without dinner.

Now, with communication, solving this problem becomes super trivial. The hunters would just get together for beers and a meal, and they would talk about it over a pint. There’s kind of an asterisk on “trivial.” It’s not actually this simple. You need a lot of cultural and reputational infrastructure for this to happen. But once that’s in place, it becomes very simple. You can also do fancy things like agree that each Tuesday throughout autumn you’ll each hunt rabbits, because boy do their fur make warm hats for winter.

Exiting the Frame

Now, the thing about game theory is that game theory is a discipline that is founded on the bracketing of communication. The signaling game concept, for those who are familiar with game theory, you might say, well wait, there’s a kind of game that doesn’t bracket communication.

Well, the signaling game is an invention of David Lewis, who was a philosopher working on language, that was imported into economics and game theory. And it’s also not really “just another game.” A signaling game where you can communicate is not really on the same class as, let’s say, a stag hunt versus a battle of the sexes. Rather, there’s “all game theory where you can’t communicate,” and there’s “all game theory where you can.” They’re radically different classes or forms. Communication throws a major wrench in game theory that can’t be neatly contained. And we actually don’t have good game theory premised on communication, but I think this is something that’s worth moving towards.

Now, I learned all this, that game theory is a discipline founded on the bracketing of communication, when we adopted a cat. We adopted Ripple in Wisconsin eighteen months ago. She loved it out there. She was outside all the time, and then we moved to New York City.

So now she’s a little pent up, and we start letting her out of our first floor window, and there’s some problems. After dark, a lot of other cats come out, especially in that kind of twilight hour, and there’s some risk of injury or transmission of disease associated with street cats. There’s also just, it becomes much harder to locate Ripple after dark, for instance. We didn’t want her to roam too far, because we live right next to an open subway track she could easily stumble on. It’d just be nice if she stayed within a closed radius, but we really don’t have any way of enforcing this. We either let her out—either the window is open, and she goes out—or we keep her inside. Maybe over many iterations of this game, we could train her in some very basic ways. It would be expensive and time-consuming.

But this is actually solved problem in 20th century suburban life, which is that the mom says to the kid, be back home by dinner, and don’t go further than the railroad tracks, and then if the kid is caught breaking it, he’s grounded. A contract and set of terms are spun up and communicated and then followed. As soon as you have language, you can coordinate much more effectively and flexibly, you can rig up more intricate coordinations.

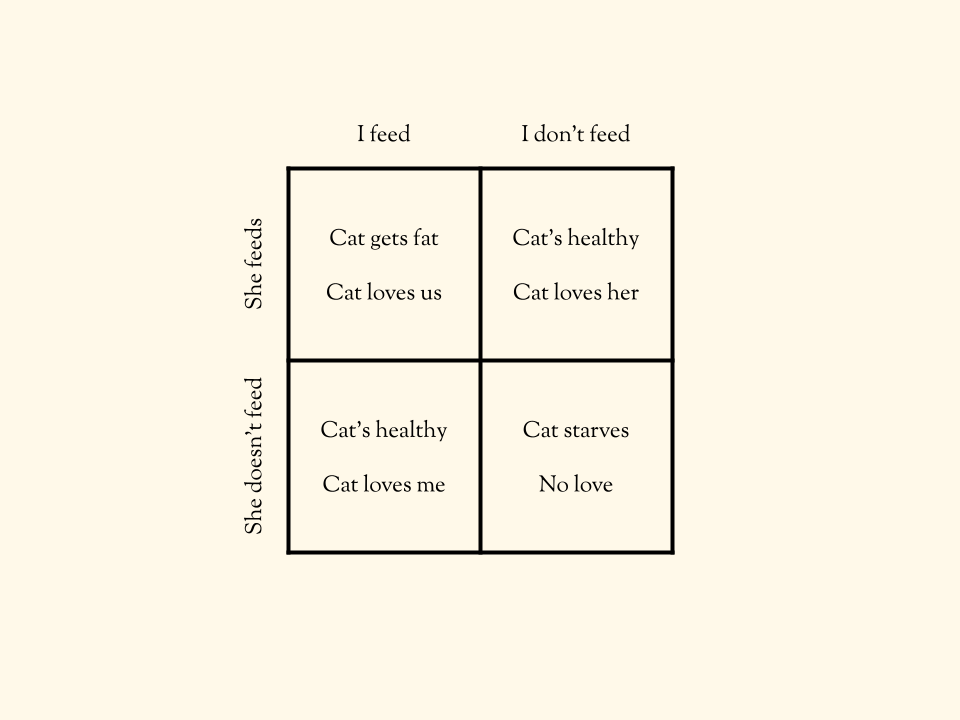

To give another example, my partner and I were trying to figure out who would feed the cat, because the cat will preferentially love whoever feeds her. And here’s the payoff matrix. If I feed and my partner feeds, the cat loves us both, but the cat gets fat. If neither of us feed her, then it’s at least fair, but the cat will be dead. And then the other two options are kind of unfair, lopsided or asymmetric, but at least the cat’s healthy.

So obviously we have to pick one of these, right? This would be the assumption of naively applied game theory. But this is a false assumption, because as I gestured at before, there’s this linkage between games and frames. Games are artificially constricting and make a small world through simplified ontology. Here there are two options, feed or not feed. It’s a binary. There are only four possible moves.

This is just not how reality works. In fact, I can feed the cat in the morning and my partner can feed her at night, or I can do wet food and she can do dry. We could alternate days and weeks. We could improvise every day; we could just say, hey, have you fed the cat yet? Various reasons to prefer or not prefer these, but the point is that that reality is incredibly rich.

We can use the richness of reality as a resource to decompose a game or frame’s artificial ontology and find more desirable solutions. And I think this is really where language comes in and starts shining, because I don’t think you can do this very effectively without language.

Language, then, increases our adaptive collectivity. With evolution’s long timescales, you can get all kinds of intricate symbiotic relationships. They take many millions of years. Massive amounts of pain and suffering are required to get to a resting point of mutualism. But communication allows organisms to very quickly enter, modify, and exit coordination equilibria on very short timescales. Communication and intelligence are linked insofar as they’re both inextricable as means of increased intragenerational adaptivity. General intelligence, or the kind of flexible intelligence that humans are often cited as having uniquely, lets us be more and more adaptive. We then change the world faster and faster because that’s our preferred pace, and gives us comparative advantage, driving our evolution into ever-greater flexibility. And the same thing happens with communication. I don’t believe it’s coherent to talk about life that doesn’t communicate. I don’t believe there is a living creature that doesn’t communicate and constantly read from and write to its environment for its own self-perpetuation. I think this is basically definitional to what life is. There’s only a spectrum of flexibility and sophistication.

Coordinating Meaning

So I’ve been throwing out vibes, but I’ll get a bit more concrete and precise in defining Lewis & Clark linguistics. I think there are four key components:

- Communication is a form of joint action undertaken to solve coordination problems.

- Being a form of joint action, communication itself poses coordination problems.

- Conventions are recurring solutions to recurring problems.

- Language is a system of communicative convention.

So we’re trying to solve real coordination problems in the world like meeting up at the same place at the same time. What that requires is that we coordinate the relationship between the words we use and the actions we then take. We’re maintaining regularities in concomitance, and others rely on us maintaining those patterns, which is to say, cooperating. If we don’t coordinate those actions, if we say something to somebody and then behave in a way contrary to the expectations that speech creates, we are functionally defecting on people. And again, there are two layers. Coordination in order to coordinate.

Let’s take a classic maneuver for coordinating and negotiating new communication agreements about how words should be taken. Everyone’s seen in academic papers the phrase, “For our purposes, we will define da-da-da as da-da-da-da-da-da-da.” They’re asking for our cooperation.

This is also why Miller’s Law of Communication is important. In order to understand what someone is saying, you must first assume the person is being truthful, and then imagine how it could be true. Miller’s Law is an ethno-method, a self-manipulation tactic, for getting yourself to cooperate fully. I think we often unconsciously resist full cooperation because of misalignment margins. We do it in a way that’s plausibly deniable, but nonetheless is a sort of conflict or aggression. I think this is part of what Bruce Webber’s non-violent communication talk yesterday gestured at.

There’s a 2009 study with a young child and an adult playing with toys together, and they establish a system where if the adult points at a toy, the kid puts it away in the box. Now, if the adult leaves, and a new adult comes in and points at a toy, the kid doesn’t put it in the box. The child understands a custom contract has been entered with the original adult about what language, what a pointer finger, “means”—what kind of actions should follow from that gesture.

Similarly, Herb Clark shares the following transcript, where two people are cooperating on a task.

A: a docksider

B: a what?

A: um

B: is that a kind of dog?

A: no, it’s a kind of um leather shoe, kinda preppy pennyloafer

B: okay, okay, got it

From here on out, speaker A doesn’t call the shoe a docksider, he calls it a pennyloafer, and speaker B matches in turn. And if you rig up these cooperation games so that one of these two participants is designated the “lead,” and the other as “follower”—we’re back in the language of dance—then whoever is the lead has a stronger influence determining what the kind of meanings and references are.

This is something Pierre Bourdieu talks about a lot in Language & Symbolic Power. Like all negotiation, linguistic negotiation is power-laden, and the dominant party typically has a stronger influence on setting the meanings of terms. In fact I think this is sort of tautological. I think a fair definition of dominance is that you get favorable outcomes in coordination equilibria that you’re negotiating for. That others will often even preemptively cede to your proposed or preferred terms.

Recurring Solutions to Recurring Problems

But most of the time you don’t need to negotiate meanings on the fly, because most of the time they’ve been pre-negotiated. This is that aforementioned cultural reservoir of resources. One of these reservoirs we call “the English language.”

We don’t have time today to get into convention—I initially made some slides here called “Plato versus the Gals” that talks about tables, rolling pins, t-shirt sizes, and oven temperatures as conventions. Regularities in the world we maintain and depend upon. But suffice it now to say that conventions are recurrent solutions to recurrent problems. And that convention characterizes both the linguistic and non-linguistic levels of coordination—in other words, that we use conventional linguistic means to negotiate conventional solutions to conventional coordination problems.

Conventions can be and are frequently stacked. If we can expect a conventional environment, we can make conventional decisions on top of it. A baking recipe will regularly refer to a rolling pin. Bakers learn various rolling techniques for different kinds of dough. Conventions are tactics, technologies, social practices used for getting things done. They’re structures of concomitant perceptions and actions.

We say, “This type of problem constantly shows up, here’s a type of solution that you can regularly employ to solve it.” And because problem and solution are regularly paired, if somebody gestures towards a type of solution, you can often infer the type of problem they’re dealing with and vice versa. Conventions are a little like decision rules in LessWrong parlance, so you need some kind of conventionalized or typified notion of what “this” is, that corresponds to a typified notion of “that” response. If this, then that. I’m handwaving much of the process away because we don’t have time.

Now, this understanding of correspondence or concomitance between problems and solutions, or references and referents, doesn’t always exist at the level of culture. It can also exist as a contract between two people, such as the kid and the adult cleaning up toys. There is some requirement of a functionally equivalent frame between coordinating individuals, and crucially, to reach this shared frame, information isn’t “transferred.” Information isn’t a thing; we can’t see or handle it. Rather, we align information.

And so often, when individuals communicate, they’re not so much trying to solve some immediate coordination problem, as they are trying to increase their shared reservoir of coordination resources. They’re trying to empower themselves for future situations, future problems, because they trust that they have a future interacting, which makes this stockpiling worthwhile. So much of what people are doing in interaction is about laying the grounds for future coordination.

So let’s consider dating. Crucially, dates usually involve some shared experience, some kind of objective cultural event that can be held as a constant. It could be a dinner, a movie, art gallery, museum.

And also, dating typically involves a lot of talk and a lot of this talk is about cultural background: where did you grow up, what kind of worldview do you have, trying to understand the other person’s mental model. But then a lot of the talk is also about the shared object of experience. You’re triangulating against a constant; you both experience the same stimulus but you have very different impressions you pull out of it. And now you build a shared vocabulary together for talking about this type of object. There’s a convergence of frameworks.

What is this kid doing? He is pointing, to pick out a subset of the environment, and he’s probably naming it. Maybe he saw it in a book and he thinks maybe his friend doesn’t know the name. They’re establishing common knowledge. He says “oh, that’s an antelope” and his friend echoes it, or agrees, or dissents. And now they can both talk about antelopes. This is how they slowly sync up their models so that they have more affordances for communicating. You could also say they’re building a larger vocabulary for drawing up agreements and contracts.

In part they’re updating their global schema but they’re also updating a shared local schema, or “frame,” or “common ground.” For the sake of time, I’ll have to handwave and blow by it but I think of a frame as an orientation to an environment or to an interaction within that environment. Goffman discusses details in Frame Analysis. And again the frame has this correspondence with the game concept. Another way to say it is that a frame is a sort of hyper-dimensional contract. With the kid picking up toys, there was a frame for how to interpret things with that adult that was a result of the contract that had been drawn up and that’s also the game they’re playing.

Species of Coordination

I’m not sure a satisfying systematic taxonomy of coordination has been attempted. But it might be useful to give some examples.

Stigmergy is a classic one. Stigmergy is (more or less) coordination in which no excess action (in the form of communication) is required to effectively coordinate. A classic example is the termite nest: the standing state of the environment of the nest is sufficient for the next termite to decide how to add on to it. The termites aren’t communicating to coordinate additions. Now, I find a lot of the stigmergy literature incoherent, so I’ll give an even simpler example, but one which, like the termite nest, nods at the way stigmergy typically requires some rigged-up correspondence to work. So let’s once again consider the tail light. True, there are cases where you hit your brake only to communicate with people behind you. But every time you brake you’re not also in addition telling people behind you that you’re braking. If I brake, and you see my tail lights and brake in turn, we’ve coordinate stigmergically. But it only works because the brake is wired up to the tail light. The game has to be rigged up for this to work.

Piaget, who studied children’s play, contrasts ordinal coordination—where this follows that—with additive coordination, where this goes with (concurrently) that. Now, in real coordination, these two types are constantly intertwined in a continuous way, but this distinction helps us understand the difference between, say, tacit coordination and stigmergy. Tacit coordination, like meeting at the Grand Central information booth at noon, is additive coordination with no excess action in the form of communication. And stigmergy is ordinal coordination without excess.

Piaget also tells us that when we count a group of stones the math is not in the stones but is our process of acting in response to them. So logic to Piaget is merely an associative structure like language or a kind of metaphorical set of rules and procedures that we follow. This paves the way for an action-oriented theory of math. Or really, a Lewis & Clark model of mathematics as joint action.

Every utterance stakes reputation

Earlier, I put an asterisk on the stag hunt, and we can unpack that quickly. My basic claim is that every utterance or expression we make actively bets, and is backed by, our reputation. The same way that the default sacrifice in ritual is time, the default stake in communication is reputation. And reputation functionally cashes out as “the ability to partake in and influence negotiations over future coordination equilibria.” Four main points here:

- Language allows us to enter contractual agreements

- Reputation-tracking gives these agreements weight

- Agreements change the payouts of future actions

- We observe agreements out of self-interest

One of the ways that we increase alignment between agents so that they cooperate is by making sure that their actions here and now, in “this” game, spill over into future games. If they defect, that will jeopardize their ability to enter coordinative agreements in the future. This reputation staking lets us do things we couldn’t otherwise, like hold this conference. Schelling calls this reputation staking “self-binding.” So much of our freedom and empowerment is founded in self-constraint.

What we’re beginning to see here is that communication works by altering the receiver’s structure of expectations, that is, their model of payouts for various actions. Self-binding and reputation-staking work because it changes other agents models of what we (the self-binding, staking party) will do. They are more likely to optimize around the future we’ve represented in speech because they can be more confident that we will fulfill our side of the bargain, because it will be costly for us if we don’t.

This is where our model ties into more classic Gricean pragmatics, via the idea that every utterance implicitly promises mutual gain if acted upon in the way the speaker intends us to act.

In other words, communication is not just describing the game; it’s actively changing the game. If you look at a lot of the so-called psychological effects that come out of behavioral economics, they’re really just failing to account for the complexity of the communication landscape and the social optimization that’s happening around it. Tipping’s a good example; everyone is familiar with the Stripe or tablet-style tipping screens that have taken over, and a classic nudge example is, well, if you increase the amounts on these screens by default up to 18, 20, and 22%, rather than 10, 12, and 15%, you get higher tips.

And this is clearly true, I would never argue that you’re not going to get more money out of people, but I don’t think it’s because people have been fooled, I think it’s because you’ve communicated something to people about the world. You’ve changed the actual functioning of the game, and the meaning or payout of various gestures, and participants are rationally updating. Suddenly, a 15% tip means “stingy” rather than “generous.” Bypassing the default tip amounts, and entering a lower, custom tip, becomes an insult. The actual amount necessary to communicate a compliment, or appear generous, is higher. And I think this is very obvious upon phenomenological introspection; the cargocult methods of behavioral economics, jumping too ambitiously over steps in the rigorizing pipeline, has led them to expend more effort to get a worse explanation.

Another example: a fly gets stuck in a honey trap because it’s pursuing its own interest, which is that it thinks that feeding on the honey is in its own interest, until the soap breaks the surface tension and it drowns. In fact, it doesn’t even realize it’s being communicated with, although we’re clearly communicating with, or manipulating it, via the olfactory signals of the honey. So again, we manipulate others by creating and maintaining an appearance that a certain course of action is in their self-interest. If we’re cooperating, this impression or appearance is “true”; if we’re defecting, then it’s “false.” But either way, the appearance is what matters in influencing the receiving agent—a “true” claim that doesn’t appear “true” won’t be picked up, for instance. This is the realm of opticratics, which I’ve discussed in the past.

Ontogeny Recapitulates Phylogeny

The final section of this talk is a bit of a swerve. “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is a line from Ernst Haeckel that a lot of people are probably familiar with. It has very much fallen out of fashion. The basic idea for Haeckel was that if you look at the way that embryos develop, they recapitulate the stages of evolution in their developmental trajectory. So it starts as a cell and then becomes an affiliated cluster or tube and slowly it becomes more and more complex. It’s ordinally correct, but if you put too much pressure on it, it falls apart.

But I think if you take it loosely, with the appropriate level of grip, as a metaphor, it’s really useful in understanding communication and language acquisition and how there’s a parallel between the evolutionary and developmental acquisition of language. Let’s take this Vygotsky quote on language acquisition:

The kinds of exchanges with adults that facilitate sensorimotor & later linguistic development require little from the infant at first except regularities in behavior & expressive reactions that parents tend to interpret as if they were meaningful gestures.

And Piaget makes a similar case. The child starts by babbling, and observes different behavioral reactions from receivers, and then it self-imitates and repeats and becomes habituated into the linguistic pattern. And because the parent who is training the child into a certain set of conventional associations between an expression and a reaction, because that parent is himself habituated to the cultural pool of conventional expression-reaction concomitances, the child is getting acculturated into (roughly) the same habits of expression and of reaction, of reading and writing, as the rest of society.

The way David Lewis expresses this in his work on convention is that “Past conformity breeds future conformity because it gives one a reason to go on conforming.” And this is roughly how I think signals develop over evolutionary time scales. Emissions get honed and regularized according to alignment thresholds—but also, there are treadmills of destabilization and innovation according to misalignment thresholds. You see this in e.g. the Batesian mimicry patterns of poisonous red dart frogs or butterflies.

In Conclusion

So what is Lewis & Clark Linguistics? Something like ACiC—all communication is coordination.

What is ACiC? Well, crucially I think it’s a beginning, and not an end. We perhaps have a more rigorous description that we can use to check against higher-level abstractions and coarse-grainings. Action-oriented linguistics (or ACiC, or LCC) might not be the best way right now to think about literary meaning, and novels, but it can be used as a means of auditing more appropriate coarse-grainings.

It’s also perhaps a basis for a philosophy of art and authorship. Why do we make things? Why do we speak and write? Why do we come up with new concepts? Why do we come up with new framings and narratives? How does the neologism-coining function of a novelist provide us with new solutions to recurring coordination problems?

What are some open problems in need of solving?

- Scaling up from simple signaling and speech acts to casual sociality, small talk, storytelling, poetry, and scientific theory

- Re-situating game theory within a communication-dense, ontologically recomposable ecosystem

- Better understanding frame-building & frame-breaking in solution recomposition

And what are some experimental directions?

- Refactoring emotions as expressive (communicative) performances designed to accomplish social effects

- An action-oriented philosophy of math

- Subtle communication as magic (aesthetics, seduction, rhetoric, charisma)

- An ethics of radical responsibility

In the post-Freudian therapy-speech culture we live in, emotions are something that authentically stem from inside of you. But we forget when we talk about self-expression that the major part of expression—in terms of what’s getting selected and optimized for, in terms of what’s load-bearing—is how that expression exists in an ecosystem, how it actually changes the behavior of huddled and interdependent organisms. That’s why it evolved, that’s why we learned it, and yet we bracket it out, and say expression is all about self-truth. And perhaps, in a move more compatible with Adlerian psychology, we can view emotional performances as manipulative communication, a way of getting others to bend to our will. Something strategic.

We can also think about subtle communication as a form of magic, so when we’re in the realms of aesthetics, seduction, rhetoric, vibe, the social construction of reality. I’ve explored this in a recent essay, “Fool’s Gold,” on the novels of Thomas Pynchon, and the AMC show Lodge 49 by Jim Gavin. The basic idea behind “words are spells, vibes are magic,” is that yes, communication is a form of manipulation, but it’s a form of incredibly complex manipulation. Within a very narrow band of standard practice, we can predictably deploy and receive expression, but when we step outside convention, or try to skip our usual heuristics and perform second-order modeling of communicative effects, outcomes quickly become unpredictable. So the magic lies in the unmapped, unconventional, but often quite powerful forms of communication.

Finally, Lewis & Clark Linguistics (like ACiM) potentially implies an ethics of radical responsibility. Perhaps we can’t fall back on “I didn’t mean anything, I was just stating a fact.” Perhaps it’s time to start asking why that fact demanded saying.

I’ll leave a syllabus for those interested in following up on any of these directions. Thanks for having me, and thanks for listening.

- Clark, Using Language

- Dawkins, “Manipulation & Mindreading”

- Friston, “Duet for One”

- Goffman, Interaction Ritual

- Goffman, Strategic Interaction

- Goodwin, Cooperative Action

- Hutchings, Cognition in the Wild

- James, “What Is Pragmatism?”

- Lewis, Convention

- Schelling, Strategy of Conflict

- Tomasello, Origins of Human Communication

- Vollmer, “What Sort of Game Is Everyday Interaction?”

- Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

- See “Categories as Heuristics,” tis.so. ↩︎

Leave a comment