Bateson was very interested in nontransitive comparisons, possibly because they subvert the commonsense transitivity of hierarchy and dominance which in many cases we read into the data because of our expectations. We rank sports teams for a winner at the end of the season, yet this final ranking aggregates a lot of non-transitivity in the meantime, in which the Angels beat the Braves, the Braves beat the Cardinals, and yet the Cardinals beat the Angels.

This is our starting point because the basketball fitness landscape is constantly changing, team quality is non-transitive, and these facts matter. Matchup matters—a championship team can steamroll the tournament runner-up but struggle against its eighth seed. These are facts familiar to anyone who plays anti-inductive games, Super Smash Bros perhaps most famously.

A certain lineup and playstyle gets rolled out, becomes dominant because it discovers an underpriced strategy and exploits the liabilities of other competitive teams. Not many good wing defenders in the league? Exploit it. You’ve created a spacing nightmare because your entire starting lineup shoots 40+% from 3? Get a rolling big. Their small forward can’t shoot from the arc to save his life? He’s a liability, and you can sag back while defending him, perhaps leaving him wide open to allow a double-team elsewhere. Maybe you win a championship with it.

Rival teams slowly figure out, over the course of a season, how to beat your new strategy, or at least limit its efficacy. They watch hundreds of hours of footage, break down weaknesses. When a team does well against your new lineup, coaches all over the league take notice. Trades get made in the off-season to reconfigure teams so they’re less exploitable—the value of a good wing defender just went up. And some teams try to beat you at your own game. They realize their current lineup could play decent small-ball with a few adjustments, so they pull their 6th man off the bench, trade for a more agile center, change their spacing.

Nowadays, the league’s gotten small. Centers have been selected for agility, are better shooters from distance, to improve spacing. And this creates a fitness landscape where no one can defend a legitimate Big. Someone like Shaq in his late-90s prime could likely enter the league right now and dominate more than he ever dominated in his own day. Enter Joel Embiid.

But of course, teams would adjust again. Shaq’s tenure in the league changed lineups for years. New rules were implemented by the League to counter Hack-a-Shaq, an endgame strategy named after the player whose weakness—free throw shooting—it was designed to exploit.

From The Ringer:

The Warriors’ Lineup of Death took the NBA by storm last season. By surrounding Steph Curry with four players (Klay Thompson, Andre Iguodala, Harrison Barnes, and Draymond Green) who could switch screens and shoot 3s, they played a futuristic brand of basketball that upended conventional wisdom about smaller jump-shooting teams. Green and Barnes could defend bigger players on the block, while bigger defenders were uncomfortable chasing them around the 3-point line, especially in pick-and-rolls.

The league, or more specifically the Thunder and the Cavs, found an answer in this year’s playoffs. Those teams played faster defenders on Green who could switch the screen and stay in front of Curry, allowing everyone else to stay at home and cutting off the main source of the Warriors offense. That answer was not available to most teams, because most don’t have big men as agile as Serge Ibaka and Tristan Thompson, or wings as versatile as Kevin Durant and LeBron James.

And from The Oklahoman:

[W’s small-ball lineup] outscored the Thunder by 11 in the final 4:50 but also dictated the style of play. Coach Billy Donovan took Steven Adams out, played a group of wings and tried to match small with small. It didn’t work. Three months later, the teams meet again, this time with a spot in the NBA Finals on the line. The rosters remain the same, but the Thunder’s identity has morphed, creating a potentially intriguing contrast of styles should OKC stay big when the Warriors unleash their speed.

Donovan continues to laud his team’s versatility publicly, saying they can and likely will play varying styles. But the trade-off is simple — should Donovan go small, he’ll be dipping into his thin bag of wings at the expense of his loaded set of big men.

II.

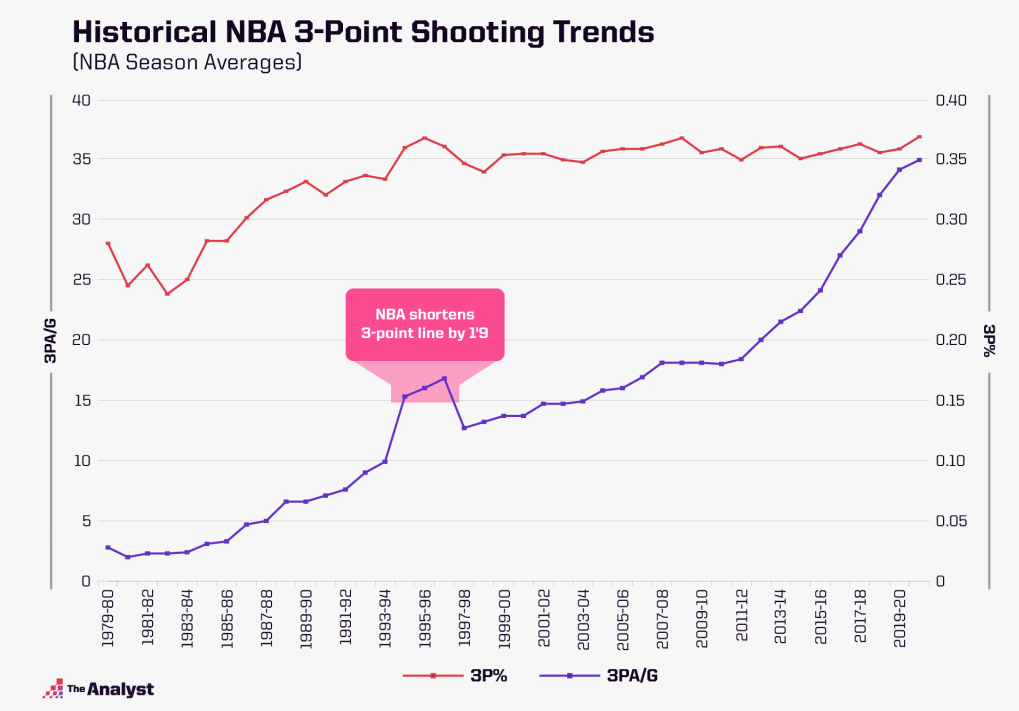

Another dynamic of note: 3pt shooting % has stayed more or less the same despite, the past decade, despite our being in the midst of a “three-point revolution”—what gives?

The league average 3-point percentage in 2005 was 35.8, and in 2020 it was… 35.8. Now, don’t mistakenly claim that NBA players aren’t better shooters. The increased volume and the increased difficulty that many players shoot with, especially off the dribble (think of that Steph dribble combo step back 3 against the Clippers and Damian Lillard’s logo 3s), are factors that definitely count toward increased shooting ability.

In other words, 3pt shots were “underpriced”—their reputation and frequency of use didn’t reflect their average returns. When teams realized this, they encouraged their players to take more and more 3pt attempts, and since “shot selection”—the quality of the look you get and take—is a thing, the more shots you take, the necessarily harder each becomes. Low-hanging fruit get taken first, which means each additional fruit is higher than the last.

To break this down, if it isn’t intuitive—if you had ten “looks” (shooting opportunities with the ball in your hands) and only took one three-point attempt a game, you could choose only relaxed, unguarded shot. If you were an NBA-level shooter, you could easily have a percentage above 50%. But you only get so many looks per game, and you have to choose whether to seize their opportunities or else look for a new look (e.g. by passing out or driving to the basket). So if you touch the ball 20 times, and shoot 10 of those times, you’re aiming to take the upper 50% of looks you get. And that means the shot difficulty ratchets up fast, from one 3pt’er a game to ten 3pt’ers.

And so, if you look strictly at league-wide %s, distance shooting ability in the NBA seems relatively balanced. There are tons of third-stringers who shoot 40% from the line, and well, if the league’s best shooter hits 43%, that doesn’t seem like a big disparity! But league-best shooters don’t get paid an order of magnitude more than third-stringers for three measly percentage point. The third-stringers are taking 50-100 attempts per season, and the best shooters are taking 500-1000 attempts—an order of magnitude disparity.

There’s an equilibrium, then, where great shooters are basically encouraged to keep shooting until their shooting % drops below like 38% and they become inefficient. This is a gross oversimplification, but the basic principle holds.

And it’s this exact dynamic, incidentally, that can get misunderstood when talking hot hand fallacy—as players get hot, the other team compensates to increase defense, and the player himself gets cockier, starts making “heat-check” attempts from distance b/c he’s on a roll. Naive statistical analysis will fail because competitive human games are “self-repairing” or “self-correcting” in a highly intelligent way, where player decision-making adjusts whenever a player is getting “outsized” or “premium” returns—these are re-iterations of the original fact, that basketball, like almost all human competitions, is anti-inductive.

III.

What are some of the factors that prevent basketball players from incorporating discovered winning solutions? That is, what limits or lessens the anti-inductivity of the sport?

(1) Indexicality of play. Players might wonder: will that move or style work for my body type, my skill-set, and within my team’s context? Any given imitable element works—fits—within a complex array of other interlocking parts, which in conjunction determine efficacy. Not every player can imitate every trending technique. Not every player can equally stop any overpowered technique.

(2) Hubris. Great players are also often the most arrogant of players, a result of—and a cause of—their success. (Jane Austen is a chronicler of hubris as a general pitfall of the clever, though we can get it with Shiv on HBO’s Succession as well.) Perpetually reinventing oneself, and looking to other players’ for new moves, requires some humility. Adopting new techniques often requires crossing a fitness valley of diminishing efficacy, players will give up on adapting prematurely, or alternatively, are not easily convinced that the play style would improve their game. There is, of course, no way to easily test or demonstrate that it does, one way or the other—it requires a leap of faith.

Leave a comment