In the Second World War, Allied troops airdropped massive amounts of food, weaponry, and supplies onto the Melanesian islands as part of their island-hopping campaign in the Pacific. To the islanders, isolated from industrialization, the wealth and abundance of these drops were interpreted within a mystical, quasi-religious framework. When the war ended, and the airlifts dwindled to a stop, cults emerged among islanders attempting to ritualistically summon more supplies. Lacking an understanding of the core mechanisms behind the airdrops — a world war, mechanized flight, the Allied island-hopping offensive — these so-called cargo cults began constructing imitation runways, dressing like U.S. soldiers, and praying that supplies would come without success.

This style of imitative practice has already been co-opted metaphorically into the concept of cargocult programming. Here, I’ll adapt it to describe a specific kind of artistic influence.

“I think ‘CargoCult’ is better used to describe situations where the current inhabitants of an organization are in awe of an artifact (piece of technology, body of code, policy, etc.) that’s… been left by ancient, venerable ancestors…” (Discussion)

Frequently, a writer, filmmaker, or visual artist will imitate the qualities of a work he admires. All imitation, however, is not equal. Any element in a work operates as a part of a whole; it functions in context, in fitness, in conjunction with other parts; and only in this way can it be understood.

Works, moreover, are applications of conscious and unconscious theories of the world; they are governed by unifying logics. Many of a piece’s surface qualities are born as byproducts of conceptual concerns, or serve as pawns for greater mechanisms; when this is ignored, when the “why” and “how” of an element is not given adequate consideration, the artist and critic are at risk of cargoculting.

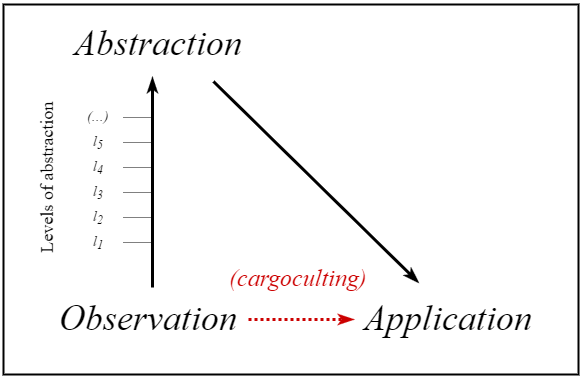

Cargoculting is an abstraction problem, a substitution of deontology in consequentialism’s place. Whereas the lower-case avant-garde abides the rule “rip up existing rules,” the upper-case Avant-Garde recycles the surface details of earlier avant-garde experimentation, ironically becoming avant-garde’s ethical opposite.

In cargocult, noisy details of complex systems are removed from their original context, so that the abstracted rule which makes works “work” no longer holds true. To understand and therefore learn from a work of literature, music, or art, one must traverse from the specific to the general, must get at the category of mechanism which each part obeys in its relationship to the whole. This is the difference, in admiring the tailoring of a suit, between copying the exact measurements of its cuffs and copying the proportions of its cuffs relative to jacket and frame. Effect derives as much or more from underlying principles and coordination as it does from the principles’ resultant specifics. Avoiding the cargocult of literature and music necessitates a move away from words or notes and toward their system-oriented mechanisms, for only then can an imitator appropriately apply learned abstraction to the specific context of new work.

Cargocult Art

To cargocult is to imitate a work’s surface structures while lacking a proper understanding of the actual mechanisms behind its power. The cargoculter builds a motorless airplane from palm fronds, sprinkles it with holy water, and prays to the gods for it to take off.

In art, cargocult frequently looks like: the inclusion of nonessential, purposeless, or even counterproductive vestigial elements, elements which have been imitated without being properly understood. Style is separated, amputated from the body of the imitated work and sewn onto a Frankenstein imitation. Choices made in constraint are treated as if autonomous, and rarely are the effects which the imitator desires transferred. Cargocult is not destined to fail —sometimes a lifted style or tic will fit snugly in new contexts. But when it does succeed it is through happenstance rather than strategy.

Analogue fetish, contemporary lo-fi, folk imitation, and a capitalized Avant-Garde tradition all strike me as generalized examples of cargocult formalized into artistic traditions. Warhol’s early imitation of AbEx “paint drips” shows an artist in his early stages cargoculting predecessors:

[He] applies paint the way an Abstract Expressionist artist would, allowing it to drip. “You can’t do a painting without a drip,” he told Ivan Karp, who was director of the Castelli Gallery. This is what I meant by saying that he used Abstract Expressionist gestural painting as protective coloration. The drips did not come from some inner conviction… (or, we might interpret, an internal logic) …they did not refer to that moment of trance when the A. E. painter moved the paint around without tidying up. “The drip”… for Warhol… [was] an affectation… (Arthur Danto, Andy Warhol p.14)

An amateur author who engages in all the niceties and stylistic flourishes of nineteenth century prose, believing it to be “proper” writing is probably engaging in cargocult. So too are those Victorian role-players who insist on wearing three-piece suits in inappropriate social settings.

It’s important to emphasize that imitation is frequently unconscious, resulting from socialization and tribal norms. Consider what makes one aesthetic choice seem entirely acceptable to one group, and entirely unacceptable to another; consider the ways artists attempt to proxy certain effects by adhering to group value hierarchies. Within art, film, and literary circles, experimental sensibility is often signaled (and understood) through non-narrative structure, self-reflexivity, nested patterns, and a direct treatment (acknowledging the physicality) of its medium. And yet these are qualities of an experimentalism long past, associated with modernist and postmodernist innovations of the 20th century. They are no longer experiments but the signifiers of experimentalism, announcements of status.

Cargocult Criticism

To judge with a cargocult mentality is to apply sloppy heuristics instead first principles, to make assessments of efficacy based on surface more than physics. The cargoculting critic sees a convincingly painted wooden airplane and pronounces it sound; a helicopter, meanwhile, will seem to him absurd.

In criticism, cargoculting is the confusion and proxying of surface for essence, of trapping for harness. A certain aesthetic style or affect is perceived as correlating with a desirable trait — perhaps acoustic instrumentation with honest self expression — and soon the two become hopelessly confused, audiences using the appearance or absence of a style as a proxy for its ideology, quality, and depth. Genuine innovation can go unnoticed, while regurgitation disguised with savvy signaling is showered in praise. The nostalgia which has swept over pop’s critical landscape in the 21st century is in part a product of cargocult. Likewise: that uncanny tendency for modern films, viewed in black and white, to transform into masterpieces. Rockism, Dylan at Newport, and midcult all strike me as examples of cargocult in criticism.

Cargocult is one form of harness/trappings confusion, where the decorative or surface-level elements of a thing are confused with, or mistaken for, its essential elements. Other essays which touch on harness/trappings confusion:

“If It Sounds Bad It Is Bad,” Suspended Reason: original explanation of harness/trappings distinction as it pertains to pop music.

“Experimental Fiction as Genre and as Principle,” Big Other: object-level examples of experimentation (e.g. bricolage, found materials, film distressing) are confused with experimental practices themselves.

Conversation with A D Jameson pt. 1, Suspended Reason: discussion of ways the avant-garde is superficially channeled or emulated.

“The Progress of Poptimism,” Rare Candy (section 4.1, “The Need for a New Criticism”)

“Scuzzy and Sincere: Imperfection in the Digital Age,” Dingus DIY: object-level examples of authenticity (e.g. low recording quality, distortion) are confused with authentic artistic practices themselves.

Leave a comment