“Only a fool swallows myths,” reads a protester’s sign, near Westminster, morn. “Keep the story of England alive,” counters a Parliament plaque, mere paces.

Drenched in Medievalism lately. Picked up Ivanhoe at a Hythe charity shop. The chivalric figure, at least in Scott’s telling, is fundamentally generous—and yet (it is like a magic penny) the more he gives away, the more he gets back. The example of his generosity inspires generosity in turn, making Girard proud.

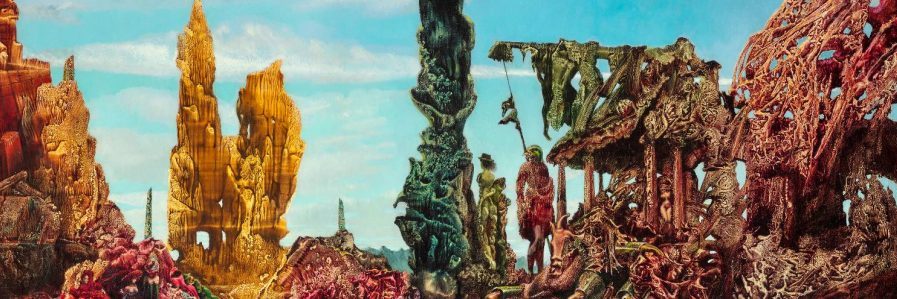

And the Pre-Raphaelites at Tate Britain—the “Victorian avant-garde” and perhaps not the reactionaries we think them now. Political radicals, aesthetic radicals, writing Modernist manifestos, compiling canons of the Immortals. They were painted en plein air decades before their more famous Impressionist counterparts. Their canvases were primed in white, and the effort often resulted in vivid, psychedelic colors—as in Hunt’s Our English Coasts.

Consider Proserpine (Persephone). She who has eaten of the pomegranate: Forever enthralled. Far from herself & her home & her love. Winging strange new ways in her thought.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti made 8 attempts at this portrait over his lifetime, working on it up to his death. Proserpine’s cloak is night itself: Black and oily as the sea, and blue, blue as her eyes. All the scene is chilled in Tartarean gray.

Jane Burden stood for the portrait as model. She was Rossetti’s muse, and she was Rossetti’s mistress. She was also married to William Morris, Rossetti’s friend. Like Persephone, Burden spent her winter months with her family—a dutiful mother and wife—and her summer months with Rossetti. He is her portly adoring Adonis. Ivy creeps behind her, the clinging of memory.

Her lips have been painted the same waxy red as her pomegranate, which stands for pregnancy and pleasure. The seeds enthrall Proserpine to bondage—she is seeded & swells—she is oppressed by her biology, in the language of modern feminism. “Goblin Market,” by Dante’s sister Christina Rossetti, treats similar symbols: the desire, decay, & fecundity of the forbidden fruit. So does Snow White, with its poisoned apple slipt from unclenched fist, rolling across the floor, a single bitemark in its skin.

Nearby Proserpine, in the gallery, we see her again, in a new costume. It is Burden again, and she is playing the role of La Belle Iseult—Tristan’s Isolde. Again we see her in a state of mourning, loss, and separation; again we see her as passive subject, as heroine retaining composure and grace in the face of events which threaten to shatter her. This time Burden is painted by her husband, William Morris, but the subtext of infidelity remains. King Mark, after all, was a cuckold.

The Pre-Raphaelites do this often; it is part of what makes them proto-Modern. They live at once in the worlds of myth and material. Types recur eternal, played by the bodies and persons, as if an actor toggling between roles. Costumed as all of us are costumed; adorned, as all of us are, in story. Burden is Beatrice; she is spring incarnate; she is Guinevere and Pandora; she is Astarte, Semitic goddess. (And Astarte is a Hellenized Ishtar.) Likewise would Elizabeth Siddal play Shakespeare’s Sylvia and Ophelia, Dante’s Beatrice and Rachel. Her red hair allowed Rossetti to explore the play of light, and kicked off a multi-decade fad across the channel.

Some of the techniques of Joyce are already present. Certainly many of Yeats’s—W.B. having grown up in a Pre-Raphaelite commune, and modeling much of his poetry on Rossetti and Morris. Basil Bunting claimed that it was Rossetti “who first wakened [Pound] to the possibilities of poetry, [his] teens… dominated by the sound of Rossetti and the feeling of Rossetti.”

Julia Duckworth, mother of Virginia Woolf and the real-life Mrs. Ramsay modeled for the painters. To Edward Burne-Jones she is Princess Sabra, fed to the dragon; and also the Virgin, visited by Gabriel. The Pre-Raphaelites would influence the French Symbolists, who would in turn become formative to Modernism and Surrealism.

In the art history many of us learn in school—both through formal instruction, and the informal hierarchies of the hip—the Pre-Raphaelites are not considered serious artists. They are “pap,” says Heronbone—fundamentally unserious, light fantasy and rococo. They are decadent Victorians, in stark relief to the Modernists to come.

If I am in a mood of strong feeling, I would say that such teleologies of art, with their pseudo-scientific airs of Greenbergian objectivity, have led the field to a dead end, to confusion and despair, to soulless commercialism and endless self-purifications. Filmmakers today are the true inheritors of the visual tradition. And they owe more, perhaps, to the Pre-Raphaelites than to the Modernists. We must rethink our forking-path labyrinth, and retrace our steps. Other paths beckon.

Other echoes

Inhabit the garden. Shall we follow?

Quick, said the bird, find them, find them,

Round the corner. Through the first gate,

That the Pre-Raphaelites lead to Art Nouveau—and by extension, to Art Deco—is uncontroversial, though the lineage is often written off as decoration. (In reality, this lineage constitutes a bold, high-modern graphic style, perhaps the most successful and developed in the West.) That they are equally important to 20th century illustration is less mentioned. It is difficult to imagine either Aubrey Beardsley, Edwin Abbey, or Frank Frazetta without the Pre-Raphaelites. By extension—since so many directors of science fiction and fantasy grew up reading pulp novels, and taping film posters to their walls—it is integral to the look of late 20th and early 21st century filmmaking.

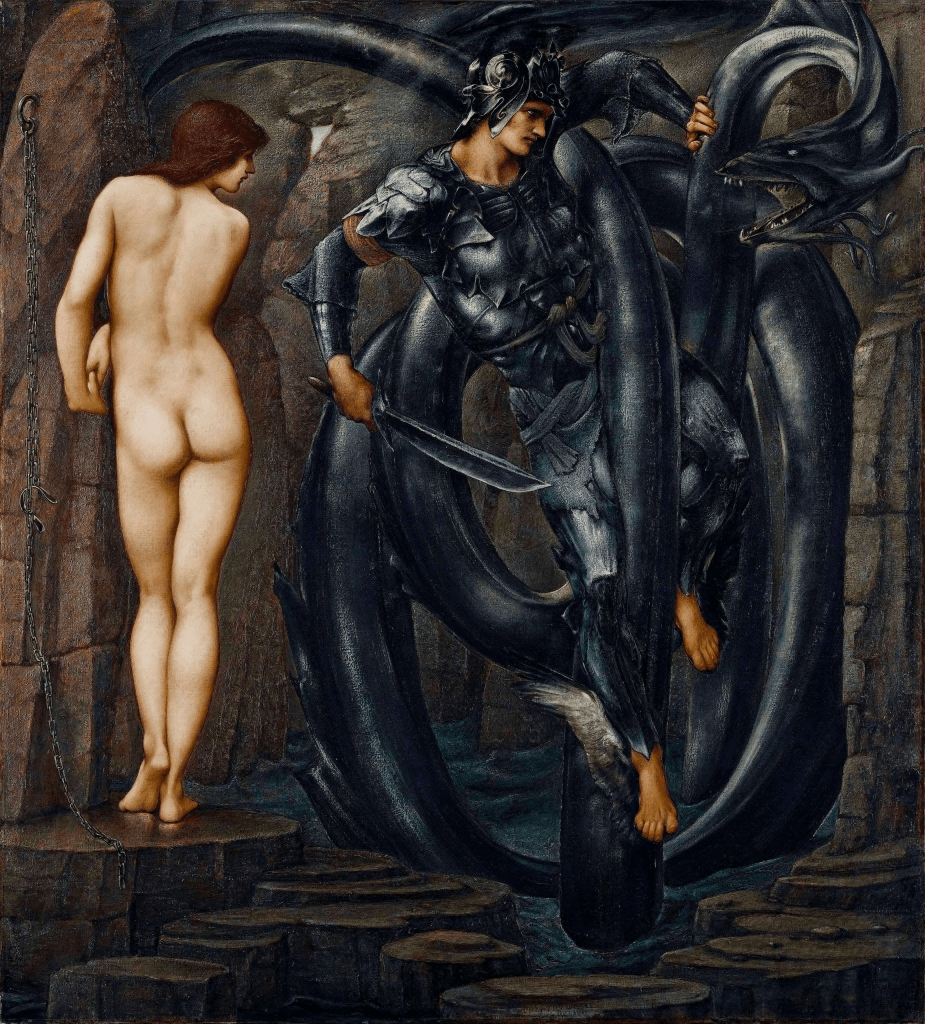

This is one of Burne-Jones’s best known paintings, from his Perseus series. Andromeda stands, nude, on the left as Perseus wrestles with the sea serpent Cetus.

Cetus is all Celtic knotwork, a Gordian knot, some Satanic writhing and reptilian thing. Curving muscle that calls to mind Scamander, Proteus, or the work of H.R. Giger which it undoubtedly influenced. Interestingly Perseus looks like the monster. He has the same dark gunmetal gray. He is soot to the virginal purity of the maiden who watches him.

He himself does not watch the maiden he is intent in the grip of the wriggling beast. The worm. He is wrestling ostensibly on her behalf, and yet he is utterly uninterested in her. Instead he is focused on the serpent which writhes phallic between his legs. (The Antichrist of Revelation is gay.)

And all these visual echoes: The monster’s face, which seems to almost be forming out of gaseous air—like some nightmare of a face bulging out from cloth or liquid skin. Rhymes with the flare of the armor on his upper thighs. With the flare of the wings at his ankles.

His blade. His armor. The Gorgon’s flesh. Glinting alien darkness. Not so distant from the oily gray seas of Persephone’s dress. As if night itself.

His helmet is the spiral of a nautilus. Andromeda is like alabaster, like a glowing lamp, like thin white marble which lets an inner sun through. Her body bears some of its same sinuous curves; she too is held to rhyme with her predator. But she is also partitioned, like the rocks around her. She is statuesque, again, marble. She is not real and to the extent she is real she is posed poised and postured. An ideal. Not actual flesh. Meanwhile the all too real sea is grey, with all the flaring curvature and gunmetal grey of the sea serpent. Paglia: “Perseus is Laocoön in the grip of coiling nature… The design recalls the illuminated letters of the Book of Kells, because Romanticism is the sacred text of nature-cult. Perseus is thrust into the hungry maw of a Blakean flower. The picture proves that Art Nouveau’s running vines are an abstract version of daemonic nature, come to aggressive life to trap and strangle the human. Burne-Jones’ brassy serpent is a scroll of Art Nouveau ironwork. The organic is invincibly metallic, while Perseus wears a visionary armour of leafy vegetation. A Greek hero becomes Spenser’s weedy knight Artegall, who keeps relapsing into nature. So we must ask of Burne-Jones’ picture: has the touch of the chthonian serpent contaminated Perseus?” And: “Burne-Jones’ serpentine line comes from Blake, whose rapacious flamelike flowers reveal the covert sexual meaning of Art Nouveau’s arabesques.” We have seen this picture before, it is the moment when a woman, in the grip of passion, wraps her legs around a man and does not permit him to pull out. Although in civilized sobriety she would be horrified, biology grips her in her passions, and we ask: Will Nature always win? This is graphic intelligence in service of an idea.

I’ll close with “The Golden Stair,” a predecessor to Duchamp’s Nude Descending the Stair. The Anglo, Germanic sensibility of the North is blended and contrasted with the warm and gentle south. (Part of the PRB’s aesthetic more broadly derives from this distinctly Anglo blending of the Latinate and the German.) Paglia calls the picture a sickening sequence of clones, a world of “incestuously self-propagating being,” and a “Late Romantic bower, shadowless under a gray sky.” Recreation without reproduction and sex without fertility, anticipating the baby vats of Brave New World.

This is a painting about our world as well, because our world is decadent. We all feel this impulse. To cloister ourselves with copies of ourselves and mirrors. To eliminate true nature, in its tense but productive dialectic, with a sterile human order. Burne-Jones sees, and shows us, how sickening this can become: a eugenicist wetdream perversion, a homogenocene apocalypse or a Nazi playhouse.

Leave a comment