Dear X,

So the bad news is I have no easy way to explain what I’m working on/have been working on/will be working on for a while. I’ve been asked about the MS a few times now and every time my answer is very different and radically misleading. The form I’m working in does not have a name, although at various points I’ve called it “illuminated manuscript,” “maqamat,” “commonplace,” and “encyclopedia.”

I’ll try to trace its origin, and then the shape that it’s taken. To skip the background context and cut to the structure, hop to the midway point (beginning with: “The structure of the text…”).

I guess at some point circa 2017 I started asking myself what it was, specifically, that text still offered over other media. Usually inquiries of this sort are not actually inquiries, they are vague, vibey, partisan defenses by people already heavily invested in the book, or the novel, or the poem. I did not want to take it for granted that the book, or the novel, or the poem was worth investing in. I was 22 years old, and I didn’t want to waste my life developing an obsolete technology.

I came up with a set of functions, or capabilities, that convinced me to stay my course as a writer. Which is awfully convenient—we go to such lengths to defend our status quo, to avoid changing. Anyway, the capabilities: One, the ability to represent conscious interiority. When I read books, I felt myself taking on, as internal voice, the tone and style and outlook of the narrator. Some cinematic or visual artworks have tried to capture internal consciousness and subjective outlook (see Impressionism) but their attempts have proven limited. If you believe as I do that the meaning of our experience is strongly determined by the conceptualizations and framings we apply—that is, the way we classify events and perceptions of events—then language is the strongest structuring force of experience available.

Two, text is highly compressive and archivally durable. It can last millennia even when stored on primitive media—sea scrolls, papyrus, clay tablets. It allows us to store not just the physical occurrences but the social, symbolic, and subjective meanings of those occurrences. It allows us to speak highly abstractly, about patterns that transcend the physical. Again, visual and cinematic formats can accomplish some of this, but in a limited and expensive way. It can take many contrived framing and reaction shots to get across a single adjective of emotion. Films can have themes, and preserve high-level archetypal patterns, but we still use language for our theories, our debates, our scientific progress. (And math is, in the sense substantial to our present argument, a form of language.)

And then I asked what it was I wanted to accomplish with text, given these affordances and capacities. I read a book called Only Yesterday by F.L. Allen, a history of the 1920s written by Allen in the twenties and early thirties, contemporaneously. There were all these details—the cut of the dresses, the way women applied powder and makeup, attitudes towards forms of recreation and work—that I realized were missing from most historical records. The very flavor and texture of life, the specific details of a culture in a moment in time—these were things I’d only seen represented in novels. I realized our culture, every culture, is in an ongoing process of extinction. It is always dying out and being replaced.

Somehow, I wanted to preserve a record of my era’s world-feel. I browsed Are.na channels named “The 2010s” and noticed that all the examples they gave, of what the 2010s felt like, seemed remarkable rather than banal. All the taken-for-granted context was disappearing because we found it unexceptional. I pictured a zip file, pictured the way that, when you export an Adobe project, it comes packaged up with assets. The index file references out—this asset here, that asset there—but lose the assets, the context disappears. I remembered a Bourdieu line:

One of the major difficulties of the social history of philosophy, art or literature is that it has to reconstruct these spaces of original possibles which, because they were part of the self-evident givens of the situation, remained unremarked and are therefore unlikely to be mentioned in contemporary accounts, chronicles or memoirs. It is difficult to conceive the vast amount of information which is linked to membership of a field and which all contemporaries immediately invest in their reading of works: information about institutions—e.g. academies, journals, magazines, galleries, publishers, etc.—and about persons, their relationships, liaisons and quarrels, information about the ideas and problems which are ‘in the air’ and circulate orally in gossip and rumour.

“The Field of Cultural Production”

I was also, concurrently, digging for many years into academic theory—philosophy, sociology, anthropology, psychology, metascience, literary theory. Whenever I entered a field, I found myself frustrated. Elementary mistakes, like confusing map and territory, seemed to be made with regularity. The fields were defined by decades-long conflicts between positions that seemed perfectly compatible. Dominant methodologies were laughably unscientific, cargoculting rigor through the misapplication of statistics.

And then, inevitably—just as I began to feel crazy, just as I began my inchoate stumblings towards articulating these felt critiques—I would discover that my objection was known. Not widely, or universally, but respected figures in each of the fields had systematically levied these same complaints, and proposed the same solutions. But mediocre practitioners, uncritically sleepwalking through orthodoxy, always outnumbered—and often drowned out—these voices. I remembered an old Peli Grietzer line from Amerikkkkka—”Kill me now: the reason the humanities are so bad is it’s so hard to find out who’s genuinely good at the humanities that only people who are genuinely good at the humanities can do that.” I read an Olah & Carter paper on what they termed “research debt”: the “mountainous climb” that is required to orient within a field and make progress. The debt is accumulated as a result of poor exposition, half-digested ideas, bad abstractions, and a poor signal to noise ratio of published research. It wasn’t that important conceptual progress was absent from these fields. Rather, tracking this progress, and reconciling the many different frameworks being used (even within a single field) to make this progress, was an enormously difficult task.

I began to think of this as a knowledge logistics problem, a term I inherited from John Nerst. The research debt was not just a problem within fields—it also made cross-disciplinary progress difficult. Skipping between such a broad array of disciplines, I found that the same concepts were being invented over and over again, by theorists and researchers in markedly different traditions, without anyone realizing. I became obsessed with the idea of acting as a diplomat, a peace-maker, a compatibilist reconciler who found these connections, who tried to assemble a great store of discovered knowledge in one place, so that they could be synoptically surveyed, and their resonances uncovered.

In 2016, I’d learned about older literary formats like the commonplace book and the al-Andalusian maqamat. Each, I realized, was an instance of knowledge logistics. In the commonplace book, readers would copy out passages from texts they encountered, organizing them by theme, and interspersing or juxtaposing them so that the different authors might “speak” to one another. The maqamat, meanwhile, was fundamentally a book of knowledge, much like similar collections of stories and fables from around the world (I am thinking of the Kalīla wa-Dimna). The author might spend decades collecting local sayings, folk knowledge, court rumors, the ideas of fellow poets and prophets and ancient thinkers.

I also realized that these authors were in the business of assembling parts and stitching them together, or “framing” them—the literary term here is a frame-tale, as in Arabian Nights. There is some formal device or frame—the King’s wife telling a story each night, and ending on some cliffhanger so that she might be spared from death—and this organizes what would otherwise be a disparate collection of parts. I remembered, in 2015, reading Maggie Nelson’s Argonauts, at a time when I had no exposure to queer theory or child psychology or the New York vizarts world. I’d found it thrilling to plunge into the gestalt way of seeing that Argonauts presented, to be transformed by a new concept-constellation. And I now realized, retrospectively, that Argonauts had created this gestalt by assembling many long quotations and inspirations pulled from other texts. That it felt, in many ways, like a synthetic commonplace, pulling many fragments from the world and stitching them together with the needle of narrative.

From here, everything flowed quite naturally, and felt inevitable. I had written two books already, La Vento and El Morado, each of which interspersed my own writing with the writing of others. In La Vento, there had merely been so many passages and blog posts and essay fragments I’d loved and wanted to somehow memorialize and include, like in a scrapbook. In El Morado, I’d picked up from Nelson’s Argonauts—I’d read Bluets, and then gone back into Nelson’s influences, and discovered the long lineage of queer, vizart-adjacent New York writers who had been interested in fragments and collage. But now I understood how many millennia of literary precedent there was for these so-called “modern” and “avant” techniques. And I became very interested in trying to contextualize, and find precedent for, aspects of modernity which we saw as exceptional or unique. I read Habermas on modernity, and read Steven Moore’s exceptional two-part history of the novel, which argues that the novel does not begin with Cervantes but is as ancient as recorded history—giving examples of Greek interplanetary sci-fi, Roman pastoral romances, and, I discovered, the Hebrew-Arabic maqamat.

I kept coming across examples of thinkers, from times we now view as golden ages, who believed they were in a moment not of civilizational peak, but decline. All around me, I saw hazy, fond, wistful portraits of the Fifties, the Sixties, the Seventies, the Eighties, the Nineties, the Oughts. I saw artists and musicians who turned away from the technological affordances and cultural condition of the present in favor of re-enacting some projected past—artists who, in the very same breadth, castigated the default plugins of Logic Pro while geeking out over digital synth presets from the 80s. I wondered whether an “exceptional present bias” undergirded so much of our collective nostalgia, the very nostalgia which unites the contemporary political left and right, the taken-for-granted premise that belies all their apparent disagreement.

I wanted to create a work that honored and participated in these ancient lineages, while also capturing and preserving the richness of contemporary culture. I wanted to escape and transcend the provinciality I saw all around me—of subcultures, political parties, academic fields and subfields. Of Dimes Square and Dissensus and LessWrong rationalism and Ribbonfarm postrationalism, of the architecture world and the visual arts and the Santa Fe Institute for complexity studies. I wanted to reconcile scientific accounts with the mythological accounts I found compelling in religion, in Jung, in chaos magick.

The structure of the text is as follows: twelve books, ninety-six “gates” (or chapter-sections). The gates range in length from a few pages to several hundred pages. The books are organized and titled according to somewhat abstract but archetypal themes: the Book of Streams, the Book of Gardens, the Book of Cycles, the Book of Games, the Book of Bowers, the Book of Machines, the Book of Divination, the Book of the Wilderness, etc. In addition to this primary organizational structure, there are hundreds of hypertext-style “wormholes” scattered throughout the text, so that it can be navigated in a graph-like, non-linear way.

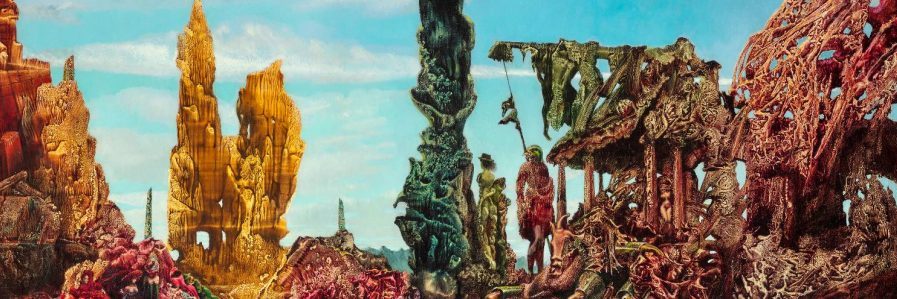

The text is illuminated, in the tradition of many ancient books, including several of the maqamat. There are hand-illustrated frames and historiated letters and countless drawings and images scattered throughout the text. A few of these images have been generated by machine learning, some of them have been traced from existing patterns and photographs, and most of them have been drawn by hand. This became necessary when I butted up against the limit of simple text—when I found it difficult to describe in words the shape or look of something I wanted to preserve.

The gates’ subjects and stylistic forms vary greatly. There are poems, and plays, and encyclopedia entries, and commonplace collections, and autofiction, and genre fiction, and art criticism, and that nebulous genre “theory.” There is a one-hundred page, second-by-second, blow-by-blow recap of the film Ex Machina, which describes the clothes the characters wear, and riffs on the semiotics of the tequila brand they drink, and they ways they groom their facial hair. There is a play which re-enacts Waiting for Godot, but with stoners waiting for their dealer to show, while they kill time rolling spliffs and arguing over the minutiae of smoker etiquette. There are riffs on gardening, and weather, and homeostasis, and natural selection. Algorithms from statistics and computer science are brought in and domesticated for everyday use. Messageboard dramas are re-enacted in painstaking social detail. The microgestures and facial expressions of viral TikTok videos are deconstructed. Thousands of items in the Lagunillas market are listed by booth; a hundred brands of boogie seltzer and canned iced coffee are categorized by color scheme, target audience, and ingredient list. There is a stand-up comedy show, and several party reports, and a mini novella about the crypto scene inspired by Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge.

The hope is that together, these texts add up to a reference text that can be lived alongside. There is always something more, something the reader hasn’t come across, something that will be surprising and unexpected. The gestalt that unites these topics, and guides their treatment, is itself a subjectivity, a perspective on the world that can be psychically occupied. And perhaps, between these disparate parts, a better document of our age might be left behind.

Leave a comment